I can vouch for the fact that the migrants who had a member or a relative in the Army had to suffer much less in 1947

My grandfather, Bedi Amar Singh, served in the 11th KEO Lancers as Daffadar for more than 30 years, including his field service in the North West Frontier Province and France during World War I. Since my father was serving at Bengal Engineering Group (BEG) and Centre, Roorkee, we, including my grandfather and the family of his elder brother, shifted to the refugee camp set up by the Army. The barracks were converted into living quarters for a large number of uprooted families of jawans and officers with minimal facilities of water and toilets outside the barracks.

When our family left home in Mandi Bahawaldin near Lahore in August 1947, my elders believed that once the rioting was over and the situation became normal, we would return to our homes. So, my parents locked the house and left the keys with our friendly Muslim neighbours, giving them charge of our cattle. When it dawned a little later that we could never go back and that we had in fact lost everything, it was quite traumatic for the family.

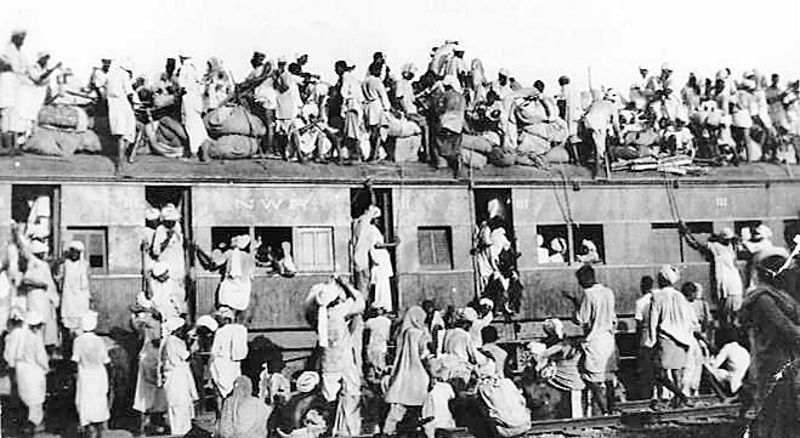

I was only four at the time of Partition but some of the incidents I was witness to are etched deeply in memory. For those living in Mandi Bahawaldin, the closest railway station was Lalamusa. Stories of communal violence, fires and the news of the murders of people known to our family used to be the subject of most of our conversations. We were lucky that in our extended family, there was no loss of life and no physical injury was suffered by anyone.

My early memories relate to the primary school I joined at Roorkee Cantt located near our refugee camp area. The fog of the tense communal situation, imagined fears and hatred against Muslims were reflected in our small talk and the games we played. Children seemed to enjoy shouting “Hath mein beedi, moonh mein paan, chal mere bhai Pakistan”. Most of us at the camp were Sikhs and it was assumed that beedi and paan were the marks of a Muslim, and the right place for the Muslim was Pakistan.

Unit games were organised for troops of BEG Centre as an annual ritual. What interested us more was the race organised at the end of the meet for the children of the troops and those living in the camp. I came first in 50 metre races. The prize distribution ceremony took more time and I was quite late to reach home. My mother scolded me but when I told her about the prize, showing her the tin of sweets, she hugged me with a broad smile.

Soon thereafter, my grandfather and his brother were allotted 30 acres of agricultural land with two mango gardens at Sandhora village in Naraingarh tehsil of Ambala district. Interestingly, in lieu of the house we left in Pakistan, we were allotted a big deserted masjid where we stayed till 1954. Living there was quite an experience. Drawing water from the pucca well outside the masjid and filling a big circular copper tank through buckets was a regular duty we children enjoyed. There being no electricity, food was served by sunset. And then, it was story-telling time as all of us brothers and sisters gathered round our mother.

The promotion of my father as Jemadar (now called Naib Subedar) was an occasion to celebrate. My grandfather was very happy to see his son become a JCO. After his six-year posting at Delhi, where I had my school education, his new posting in 1960 brought us to Ambala Cantt. Our house was near the Air Force Station. During the 1965 war, it was the main target of the Pakistan Air Force. This war was a turning point for me as I was commissioned into the Corps of Engineers as 2nd/Lt. A memorable event was the visit of Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, the Western Army Commander, to my wedding in 1971 at Delhi, since my father was on his staff. The sword which he presented to me is a cherished memento.

During the anti-Sikh riots in 1984, I was posted at Kanpur. Since there was no military married accommodation available, I was allotted a rented accommodation in the civilian area at Swadeshi Cotton Mill Colony near Kidwai Nagar. The Sikhs became the target of ferocious mobs. Many were actually refugees from Pakistan who were rehabilitated in distinct colonies. I remember when the riots erupted on October 31, one of my worried Hindu friends came to ask me to shift immediately to the Army area. It was a nightmare. I managed to call my course-mate, Maj Suraj Attri, who sent a 1-tonne vehicle with an armed escort and we were evacuated safely. En route, we could see the extent of violence and damage to property. Many of my age who were not witness to the 1947 massacres appeared to see for the first time the madness that could manifest itself in human beings.

I remember how the Army made special arrangements in their barracks to house the affected persons, including civilians, and provide for their needs. You felt a loss of belonging here, but the Army’s presence, as always, brought a touch of solace and normalcy. The Army was always there.

— The writer is based in Mohali