Indian Army personnel pose for a photograph with the Tricolour on the occasion of New Year in 2022 at Galwan valley in Ladakh. PTI

https://cdn.vuukle.com/widgets/audio.html?version=1.1.0

Advertisement

Ajay Banerjee

IN March this year, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, after a meeting with his Chinese counterpart Qin Gang, described the present relationship between the two countries as ‘abnormal’. Just three days ago, on April 27, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh told his counterpart, General Li Shangfu: “Development of relations is premised on prevalence of peace and tranquillity at the borders.”

Beijing, in the past few months, has pushed for restoration of full bilateral relations, attempting to de-link the resolution of the military build-up along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) from other bilateral matters. It’s like trying to create a ‘new normal’ and ‘new status quo’ at the LAC, said a senior official.

The Chinese foreign office described the Jaishankar-Qin meet thus: “The two sides should put the boundary issue in an appropriate position in bilateral relations and work for the regular management of border areas at an early date.” Two days ago, on April 28, a Chinese Defence Ministry statement on the Rajnath-Li meeting had near identical words.

Both Jaishankar and Rajnath have not just rejected China’s assertion, but also made it clear how resolution of the boundary dispute is a prerequisite to anything else. India’s stand is that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) should withdraw and restore status quo ante as on April 2020, lest the Indian Army stays at the LAC, the de facto border.

It was three years ago in April 2020 when China started amassing troops, hundreds of guns, tanks, missiles and long-range artillery on its side of the LAC in eastern Ladakh. India responded with equal measure. Faceoffs started happening in mid-April, followed by clashes in April-end and the first week of May. Since then, troops of the two nuclear-armed neighbours have had a deadly clash in Galwan valley; both sides have fired bullets at each other; multiple physical clashes have led to injuries; tempers have got flared on several occasions; all agreements on maintaining peace and tranquillity along the LAC have been disregarded by China.

The build-up on both sides is bigger and holds greater threat than the one in 1962 as each is backed by the latest technology — satellite imagery, UAVs, long-range guns, inter-continental ballistic missiles, contemporary fighter jets, radars and, of course, nuclear weapons.

Making sense of China’s actions

Multiple opinions abound on why China chose to militarise the boundary dispute, ignoring two decades of progress at the level of high-ranking special representatives. A plausible answer is the policy of ‘strategic coercion’ and ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ unleashed after Xi Jinping took over as President in March 2013.

Maj Gen BK Sharma (retd), Director General of the armed forces-backed think tank United Service Institution, says, “Whatever China did in 2020 is nothing but strategic coercion, India has, so far, held on.” There is a pattern to Xi’s policy, adds Gen Sharma, pointing to the disputes of maritime boundaries and freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

Since Xi took over, military standoffs have ensued in 2013, 2014 and 2017 in eastern Ladakh; 2017 at Doklam (east Sikkim), followed by the one in April 2020 in eastern Ladakh. Simultaneously, during this period, China ratcheted up maritime disputes in the South China Sea. It refused to accept the verdict of the International Court of Justice at The Hague, laying down maritime territorial limits for each of the six countries locked in dispute in South China Sea.

Lt Gen Rakesh Sharma (retd), who was heading the 14 Corps headquartered at Leh during 2013-2014, adds a reason: “Till 2010, the Indian Army had limited deployment in eastern Ladakh, the PLA had no contest. However, the Army and the ITBP used to patrol at all patrolling points as per schedule.”

He asserted: “Xi’s beginning of the ‘new era’ was aimed at stopping the Indian Army from accessing Depsang and Charding La.”

For the April 2020 events, China, in 2018 and 2019, created infrastructure on its side of the LAC. “It ‘created an exercise’ in Shahidullah (Xinjiang, north-west of Aksai Chin) in early 2020 and ended up diverting forces opposite eastern Ladakh,” says the former 14 Corps Commander.

Maj Gen Sharma argues that “China saw an opportunity due to Covid-19 and made a military push to stake claim to the 1959 line, hoping it could extract some concessions from India”.

New Delhi, since 1960, has consistently rejected the Chinese offer to settle the border in Ladakh according to the line espoused by then Chinese premier Chou En-Lai in 1959. During the Xi period, China raised the 1959-line claim in 2017 and again in September 2020; each time, India rejected it outrightly.

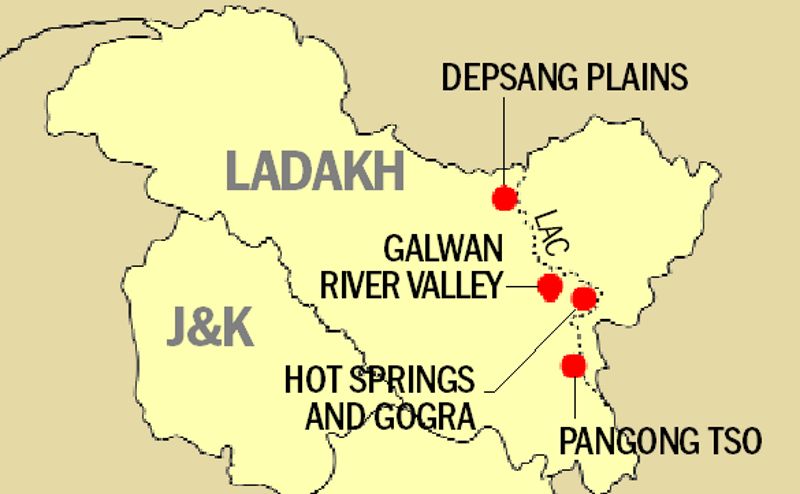

Depsang holds the key

The build-up in Depsang, a 972-sq-km plateau at an altitude of 16,000 feet, holds the key to resolve tensions. India has to hold on to it by all means. Through this plateau passes the 255-km Darbuk-Shayok-Daulat Beg Oldi (DSDBO) road that links up to the DBO advanced landing ground and further northwards to the Karakoram Pass. “The PLA’s military objectives could be to threaten the DSDBO road, attempt to cut off the DBO sector, which could restrict India’s access to the Karakoram Pass,” explains Maj Gen Sharma.

The 20,000-foot-high Saser La, which is west of Depsang, opens a route to Sasoma, and further leads to the road to Siachen, points out another official.

Keeping Beijing back

The high-profile China study group — first set up in 1975 — decided on 65 patrolling points along the LAC. In the past two decades, eastern Ladakh has been ‘militarily tailored’ to prevent a repeat of 1962. This includes adding gun positions, troops, building of roads, etc. An Indian assessment made prior to April 2020 said PLA, despite its numerical superiority and military strength, could be ‘stopped’ at the LAC. And it turned out to be true.

The Indian stance along the LAC is not akin to Nehru’s 1960-1961 “forward policy”, but mandates holding the claims line along the LAC. Lt Gen Rakesh Sharma says, “By 2015, the Army had substantially increased its spread all across eastern Ladakh.” It went on adding infrastructure and having more troops ready and acclimatised for battle at those altitudes.

The arrival of special operations planes like the C130 and C17 helped, says Lt Gen Sharma, adding that when the PLA made an attempt, “we were there to hold on and consequently build up the strength and pulled in the reserves”.

Post April 2020, the Narendra Modi government ramped up troop numbers, added equipment and even moved elements of the 1 Strike Corps at Mathura to Ladakh. A message had been sent across the LAC.

Eroding bilateral relations

Between 1993 and 2013, a period of 20 years — the timeline, incidentally, coincides with the economic rise of India and China — the two countries have had agreements which dictate the conduct of soldiers and also how a high-powered committee with members of both sides will sort out matters.

In January 2012, the two countries inked an agreement and established a ‘Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs’. It is tasked to “address issues and situations that may arise in the border areas that affect the maintenance of peace and tranquillity”.

The June 2020 incident at Galwan and May 2020 incidents at Pangong Tso fly in the face of the 2005-inked “protocol on modalities for implementation of confidence-building measures in the military field along the LAC in the India-China border areas”. The mandate is: “Neither side shall use force or threaten to use force against the other.”

The Border Defence Cooperation Agreement (BDCA), inked in 2013, says both sides have to inform about military exercises and over-flying aircraft. In 2020, China was flying helicopters very close to the LAC and India responded by flying out a team of Sukhoi-30 MKI jets.

Rajnath Singh, at his meeting with General Li, mentioned that “all issues at the LAC need to be resolved in accordance with existing bilateral agreements and commitments”. Violation of existing agreements has ‘eroded’ the entire basis of bilateral relations, he added.

Lingering dispute

The border dispute is the outcome of the fluctuations of the British foreign policy reacting to Russian pressure. As Britain and Czarist Russia expanded as part of the move described by historians as the ‘Great Game’ (1813-1907), Kashmir, Xinjiang and Afghanistan were the buffers the British created between themselves and the Russians. Ladakh and its north-eastern edge called Aksai Chin were caught in the ‘Great Game’.

In 1846, the British took over J&K and Ladakh after the first Anglo-Sikh War. Even 177 years after the British annexed Ladakh and Kashmir, the complex and vexed dispute remains unresolved. In all, the British proposed five boundaries, each separate from the other, in 1846-47, 1865, 1873, 1899 and 1914. China rejected each of them. Britain got China to send in troops during World War I and II, but the boundary remained undecided. The LAC partially adheres to one of the British-era boundaries, no more.

Undecided boundaries have shifted several times and led to confusion; each side’s claims and counter-claims have resulted in varying perceptions of the LAC. It all boils down to the perception of either side. Troops of both sides patrol the areas that they perceive as their own.

China asserts the LAC is the alignment where the Chinese troops stood after pushing back the Indian Army at the time of the ceasefire on November 23, 1962. India does not accept that. The difference in perception is of between 2 and 20 km at various points, hence the dispute. Rather, a ‘dispute within a dispute’.

Tension building up since 2020

April 2020: India notices China deploying forces across Tibet, along the LAC on its side, opposite eastern Ladakh.

April-end: First few face-offs between troops.

May 4-5: The first clashes, hand-to-hand fighting at north bank of Pangong Tso; dozens injured on both sides.

May first week: India adds troops and equipment to existing strength. Seeks help from US for procuring additional winter clothing.

June 6: First clash at Galwan valley, following which both sides create a buffer zone at the LAC.

June 15: Indian troops and PLA come face to face, a bloody fight ensues, soldiers dead on either side.

July: Disengagement at Galwan valley.

August: The Army captures the Rinchen La and Rezang La heights (Kailash range) overlooking the Moldo Garrison of China.

Feb 2021: Disengagement at north bank and south bank of Pangong Tso and also Kailash range.

Sept 2022: Disengagement at Hot Springs-Gogra.

· Pending disengagement at Depsang and Charding La.

· 18 rounds of military commander-level talks conducted.

· Once disengagement is done all across. India has suggested a graded plan for de-escalation and de-induction of troops.