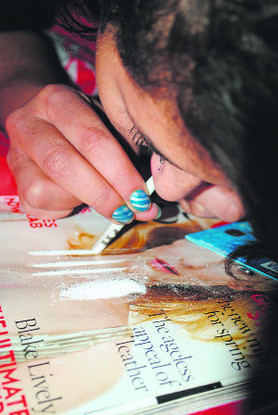

The recent heroin haul in Amritsar has once against put the spotlight on Pakistan’s continual pushing of narcotics into the country. It is as much an economic and strategic issue as it is a societal concern

The drug problem in Punjab is not about drugs. It is about Pakistan’s ‘war of a thousand cuts’ against India. It is about national security, writes Ajai Sahni

532 kg of heroin, worth an estimated Rs 2,700 crore, and another 52 kg of assorted narcotics, in a single seizure in Punjab — the largest recovery of drugs ever in India. This massive payload came unmolested across the Attari border, despite the fact that the Pakistani side has sophisticated truck scanners for the detection of contraband — bags of heroin would stand out like a sore thumb in a consignment of salt.

Read also:

The seizure of this enormous consignment of drugs has provoked the usual and contemptible political circus in the State, sparking partisan attacks on the present regime by its predecessor. Ironically, Punjab saw a decade of neglect and steadily worsening indices under the Akalis. The Badal government had, in fact, told the Punjab & Haryana High Court in 2009 that 75 per cent of Punjab’s youth and 65 per cent of all families had been affected by drug addiction; and that 30 per cent of all inmates in Punjab’s jails were accused under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act.

Partisan political conflict over the drug trade, mutual acrimony and a focus on smuggling networks and the contraband itself, detract from an essential and far more important reality that has largely been ignored: the drug problem in Punjab is not about drugs. It is about Pakistan’s ‘war of a thousand cuts’ against India. It is about national security.

More than 717 kg of heroin have already been recovered by authorities in Punjab in the current year, in addition to 285 kg of opium, 18,702 kg of poppy husk (a major source of a range of opiates), and significant quantities of other drugs. The year 2018 saw the recovery of 384 kg of heroin, 391 kg of opium, and 40,598 kg of poppy husk, in addition to other drugs. Similarly, in 2017, 192 kg of heroin, 558 kg of opium and 42,631 kg of poppy husk, among other drugs, were seized in Punjab. Normally, seizures reflect a very small fraction of the drugs in circulation, and the narcotic flows across the border into Punjab would be many multiples of these recoveries. At such a scale, the injection of drugs into the State is no less than an act of war, a lethal assault against the people of Punjab. On its own, this may still have been dismissed as criminal activity at a gigantic scale, but what we have here is the use of narcotics in a broader strategy of covert and unrestricted warfare. Narcotics are only one instrumentality that is being deployed by Pakistan against Punjab — and, indeed, India — with terrorism and financial instruments such as fake Indian currency notes (FICN) combining to devastating effect in the past, and with tremendous potential to inflict harm in the present and future.

These are not unconnected streams, but are components of an integrated, planned and sustained strategy of attrition. At the peak of Khalistani terrorism in Punjab, the entire drug trade was controlled or facilitated by the various terrorist groups that dominated the border areas, even as the principal flows from Afghanistan through Pakistan and across the border into India were managed by Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence. After the collapse of terrorism in Punjab, Afghan opium continued to be processed in factories in Pakistan and actively pushed across the border into Punjab in a conscious strategy to continue with Islamabad’s ‘war by other means’ against India.

The terrorism-narcotics linkage, as well as the ISI’s not-so-hidden hand, shows up in a number of joint seizures of drugs, weapons and, in some cases, FICN. For instance, in a succession of interlinked cases between December 2018 and May 2019, drugs and weapons, including pistols and grenades, were transferred from Pakistan to receivers in Punjab. One of the telephonic contacts in Pakistan was traced back to Harmeet Singh aka PhD, ‘chief’ of the Khalistan Liberation Force. Similarly, in May and June 2017, in two related cases, a number of weapons, including AK series assault rifles, an MP-9 modified rifle, several revolvers and pistols, ammunition and quantities of heroin were recovered, and nine persons were arrested. According to the FIRs registered in this cluster of cases, the consignments had been arranged by Lakhbir Singh Rode of the International Sikh Youth Federation and Harmeet Singh aka PhD, both under the ISI’s protection in Pakistan. The transaction was allegedly mediated by Gurjit Singh aka Gurjiwan Singh, a resident of Canada. A stream of such cases, too many to recount here, involving the combined transfer of drugs, FICN, weapons, ammunition and explosives, documents these flows over the years.

Punjab has been targeted from multiple directions, and not just across its own border with Pakistan, with drug and weapons’ flows coming from Gujarat, Rajasthan and Jammu & Kashmir as well. It is significant that, in the Attari seizure, one of the two accused is from Handwara in Kashmir.

These complex patterns and linkages are sometimes spoken of as ‘narco-terrorism’, but what we are witnessing is much worse, and infinitely more dangerous. Narco-terrorism often refers to terrorist groups that engage in drug trafficking activity to fund their operations. This is not the case with the Pakistan-based Khalistanis, who are fully supported by the Pakistani state. And while Pakistan uses drug revenues to bolster its terrorist campaigns in both India and Afghanistan, there is no necessary dependence here. Pakistan’s malfeasance would continue with or without drugs, part of its insidious strategy of protracted and unrestricted warfare against its neighbours.

Despite the very long tradition of, and substantial literature on, these patterns of war, the Indian strategic community, and certainly the country’s political executive, remain largely unfamiliar with their principles and risks. This is “warfare that transcends all boundaries and limits”, and that breaks down the distinctions between military and civilian spaces, instruments, technologies and methods. While some of these instruments can be identified, there are a range of others that meld seamlessly into the uncertainties and disorders of our time, and the insidious and coordinated energies behind these are difficult to discover and counter.

Drugs, terrorism, radicalisation, fake news, social media manipulation, disruptive conspiracies such as the ‘sacrilege’ cases – these are already part of the complex our adversaries visibly employ to bring ruination to the people of Punjab. There are other instrumentalities that an alert administration will need to uncover and respond to.

Crucially, it is now necessary to recognise this insidious way of war, and to understand that the networks of collaborators within Punjab are no less dangerous than terrorists with bombs and bullets. Unfortunately, their impact and role in devastating the State remain largely unacknowledged. Tens of thousands of petty smugglers have, no doubt, been arrested over the past years (6,622 already arrested this year; 13,959 in 2018). But the ‘big fish’, the masters of the game, remain beyond the reach of enforcement agencies. In 2014, K.P.S. Gill wrote, “powerful political patrons and controllers of the drug trade in the State have remained outside the ambit of state reprisals.” This remains the case even today. This is not just Punjab’s problem. It is a national crisis.

— The writer is executive director Institute for Conflict Management