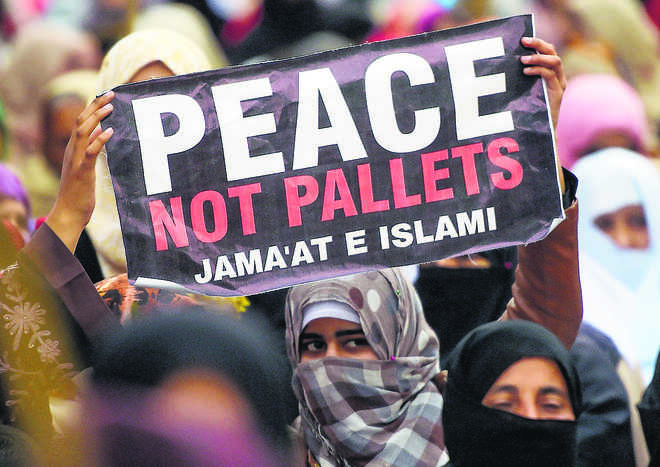

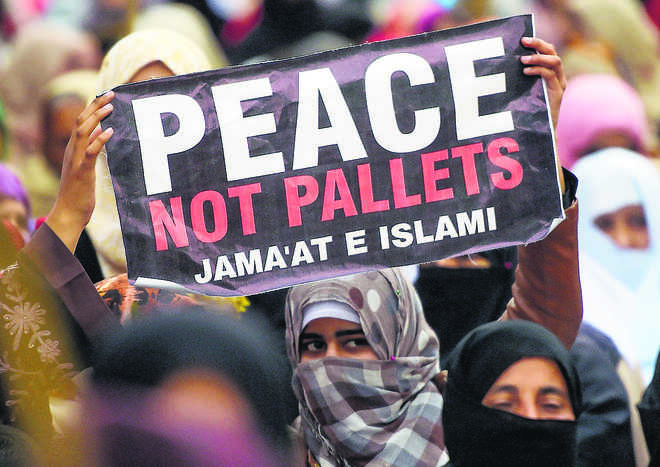

LOST CAUSE: No country will attempt to invoke the UN path on J&K, except in meaningless multilateral resolutions such as those of the OIC.

Vivek Katju

Ex-secretary, Ministry of External Affairs

OVERSHADOWING the seemingly positive interaction between India and Pakistan on the Kartarpur corridor and difficulties in working out the modalities for consular access to Kulbhushan Jadhav are Pakistani attempts at shifting the global narrative from its involvement in terrorism to the Kashmir situation following PM Imran Khan’s Washington visit last month. Pakistan obviously feels that President Trump’s offers to mediate or arbitrate on J&K and his comments on the violence in the state have provided it an opportunity to turn the spotlight to India’s internal policies and actions in the state as well as its refusal to engage it in a comprehensive bilateral dialogue.

An insight into Pakistan’s perspective of how India has succeeded in managing the narrative and also indicative of what it believes it is up against was provided in foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi’s comment at a media briefing in Islamabad last week. Qureshi said, ‘We saw how after 9/11 India very cleverly and expertly started painting the right to self-determination movement with a hue of terrorism,’ adding that ‘how India with its new alignment [in the region] and market position was able to have the other countries look the other way.’

There is no doubt that the attraction of the Indian market is a factor ensuring that many important countries do not want to tread on India’s toes. Aware that India will never countenance mediation in J&K, international players either carefully avoid offering it or emphasise that their offer is contingent on both India and Pakistan accepting it. That, of course, is a no-brainer, for the pre-requisite of any mediation is the voluntary acceptance of the process by the parties concerned. Despite the somewhat dramatic nature of Trump’s offer, the US establishment has emphasised that both countries must accept it. Thus, while Pakistan will routinely call for mediation, it will have to live with disappointment.

It is also significant that the US State Department was quick to stress — and this aspect has not received the attention that it deserved — that Kashmir is a bilateral issue. In its very first statement after Trump’s July remarks, it noted, ‘While Kashmir is a bilateral issue for both parties to discuss, the Trump administration welcomes Pakistan and India sitting down and the United States ready to assist.’ The important word is ‘bilateral’. It puts paid to consistent Pakistani attempts to portray it as an international issue to be resolved in accordance with the UN resolutions. No country will attempt to invoke the UN path on J&K, except in meaningless multilateral resolutions such as those of the OIC.

Pakistan will keep harping on these themes but its real focus to change the narrative will be to highlight the situation in the Valley in the context of human rights and India’s refusal to engage in a serious dialogue to address outstanding issues. Its entire thrust will be to persuade the international community that India’s stand of no talks as long as terrorism continues is only a ruse to continue its non-engagement approach. In addition, it will and, indeed, already is reverting to its old position of its inability to pay sufficient attention to its western border because of tensions along its eastern one. Since Imran Khan’s visit it is gearing itself to go all out in these directions.

At this stage, America desperately needs Pakistan to quickly get out of the Afghan mess. Hence, Pakistan will be indulged with soothing messages. India should simply shrug them off as it should any interlocutor who seeks to suggest how India should address the situation in the Valley. Also, it should dismiss those who may advise that an India-Pakistan dialogue should take place with reiterating its reasonable demand that Pakistan should end terrorism. Interestingly, this is a point that the US is also indirectly making.

What India has to actively promote is that Pakistan’s sponsorship of terror on Indian territory shows it to be an irresponsible state; no nuclear state has ever acted so with any other nuclear state. In this context, it must also emphasise the doctrine of pre-emption spelt out immediately after the Balakot strike. That doctrine correctly asserts that escalation towards the possibility of armed conflict that can assume dangerous proportions begins not with a kinetic response to a terrorist strike but is embedded in the sponsorship of terror itself. And Pakistan’s traditional warning against India’s use of conventional armed force under a nuclear overhang is only a pretext for continuing to use terror as part of its security doctrine.

In order to counter the international community’s sentiment that it should end the use of terror, for the new Indian approach of using kinetic force makes it much too dangerous, Pakistan is in the process of shifting arguments. It is now distinguishing between skirmishes and limited wars. It has started arguing in private settings that its nuclear threshold is not so low as to be activated in skirmishes such as seen after the Pulwama attack.

Clearly, the Balakot developments have made Pakistan feel that it can handle skirmishes so long as they do not develop into limited wars. Unlike in the past when its approach was predicated on India refraining from kinetic action after an unacceptable terrorist attack, it now feels that skirmishes will be contained and is therefore likely to project that they do not carry the risk of nuclear escalation.

Indian security managers and diplomats must take note of emerging Pakistani thinking. The unmistakable lesson is that for all its professions of taking two steps forward to India’s one, the Pakistani establishment is showing no evidence of shedding its hostility towards India or its confrontationist approach; the use of terror is an inherent part of that approach.