Very few are aware that the Indian Army follows a principle akin to corporate social responsibility (CSR). It is done all over the areas of responsibility where it is deployed operationally.

That is true for the Northeast and J&K where it has experienced varying levels of insurgency like conditions, also termed terrorism or proxy hybrid war.

During the height of the Punjab insurgency in the 80s and early 90s, my unit ensured that we did our bit for the local people in the vicinity of the deployment area. The usual favourite was construction of playing fields for educational institutions to get the youth to play; we even provided sports items from meagre funds that were available.

Also, it was broadly understood that army units had the energy, organisational capability, positive thinking and goodwill to do something for the local people.

This principle of winning hearts and minds (WHAM) through created opportunities of fraternisation and deployment of some resources came from the experience of the British Army, which used this extensively during the Malaya campaign.

The rationale for it was simple. In low-intensity conflict situations or asymmetric warfare, it’s the local populations which suffer the maximum because neither can normal lives be led nor proper governance be brought to bear.

The Army targets the insurgent or terrorist but invariably and unintentionally the population gets affected with respect to its normal routine of life, self-esteem and dignity when homes have to be repeatedly searched or movement curbed.

All this gets the population against the Army. Hence the need to make up for these privations and also assist in some aspects of development, which has been lost due to the inability of the civilian administrators to reach the remote areas or even nearer ones due to persistent threats.

In 1997, a landmark decision was taken to launch a scheme called Operation Sadbhavna. The government provided a higher quantum of funds than before with which meaningful welfare could be organised for the affected population.

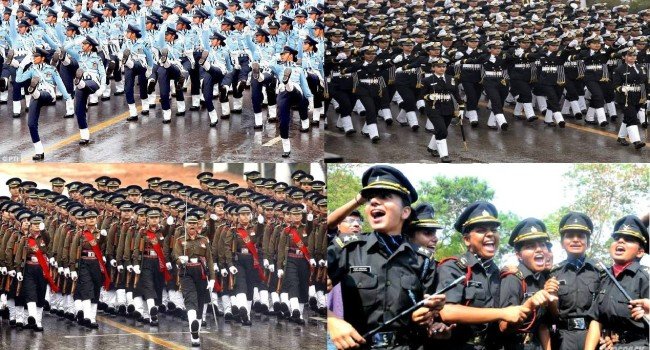

Four broad areas were selected for initial focus—education, medical aid, small-scale infrastructure and national integration. More domains were added later, including woman empowerment. In J&K the Army set up 43 Goodwill schools; they play a crucial role in providing quality education to the affected population.Through the medical aid schemes, medicines were provided for the conduct of medical camps in remote areas. Local doctors along with those of the Army attended to patients under the security provided by the Army.

It is to the Army’s credit that as part of small-scale infrastructure the first provisions for toilets for female children were made in government schools, under Sadbhavna.

Excursions for children, women, elders and other categories from time to time were organised to other parts of India to showcase progress and let the people aspire for the same in their areas through pursuit of peace.

Unfortunately, Sadbhavna is still tied down by too many bureaucratic procedures of accountability making it an unpopular pursuit for Army units who had to do both, fight the terrorist and look after the welfare of the population to prevent it from supporting the terrorist. Most units did not take this as a part of their professional responsibility, which by doctrine it is.

The success of Sadbhavna was essentially at the tactical level, except a few projects such as the Kashmir Premier League cricket tournament which helped stage 390 matches in three months and helped stave off a lot of street turbulence in 2011.

People who are unaware of the essence of counter-terror operations are today questioning the worth of Sadbhavna, not realising that it never had any strategic goals, only tactical ones to help the Army’s units conduct what is generically also called military civic action (MCA) and is an essential part of such ops conducted as part of asymmetric warfare.

The need is actually felt of taking MCA to a strategic level but be executed by many other agencies of the government in what is often referred to as ‘all of government approach’ to become one of the major prongs of countering hybrid conflict.

This will also enable outreach and engagement by the government in the manner done by the Army. Townhall kind of interactions with the population in different parts of the state with government officials willing to listen more than speak, even as medical and veterinary camps are conducted at the same site.

Post-August 5, 2019, there are quarters which feel that nothing needs to be done for the welfare of a population in Kashmir which has responded only through stone-throwing at our forces and support to terrorists.

This attitude is devoid of rationale and smacks of a lack of understanding of the larger social issues in a hybrid conflict zone. Stamina and will to persist are a must among the forces and the government servants if we have to effectively fight Pakistan’s proxy conflict in Kashmir. This is all a game of patience.

If Pakistan has the stamina to keep us engaged in a long war by a thousand cuts, it is absolutely incumbent that we must display the stamina to stem that offensive whether it takes a year, 10 years or 50.

So while the government of India effectively proceeds to unravel and dismantle the ecosystem of devious networks through its correctly perceived strategy, it must simultaneously continue to work on WHAM at a strategic level. The Army must never think of giving up on Sadbhavna which has helped maintain balance in its relationship with the people. Not for nothing is the population the centre of gravity of an asymmetric warfare campaign; always has been and will always remain so.