As the world oscillates between ‘post-truth’, ‘half-truth’, ‘under-truth’, ‘alternative-truth’… Guru Nanak’s Sach pura na hovey naahin rings out. Never, never ever, does Truth grow old. It was the very foundation of all that is good and all that will surviv

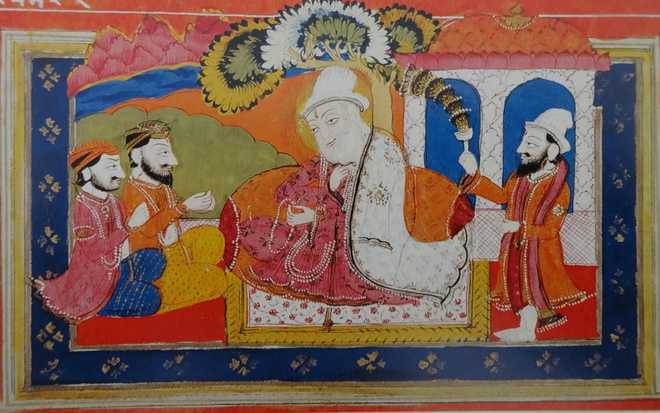

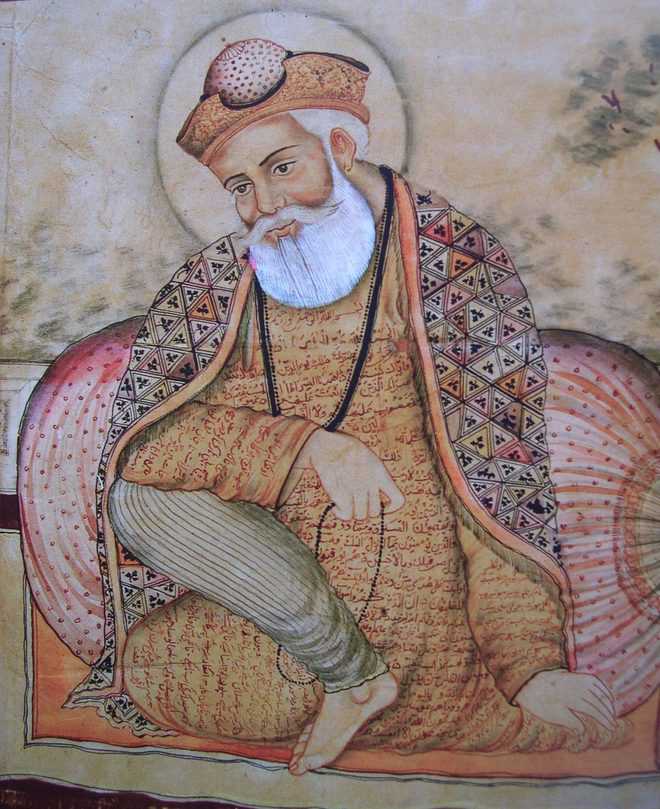

Serving a higher order: Guru Nanak with disciples and attendant. Kashmir; first quarter of 19th century. Image courtesy Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh

All-encompassing: Guru Nanak wearing a robe containing the opening words of the holy Koran. On the sleeve (see the next picture) are words from the Mool Mantra, also in the same script. Government Museum & Art Gallery, Chandigarh

On the sleeve are words from the Mool Mantra, also in the same script.

BN Goswamy

Truth, we know, is under siege in our times: everywhere, in all places, at all levels. When not altogether denied, it is being bent, twisted, left behind, knocked down, mocked at. And it seems to be about time to recall to our minds, at least now when we are in the midst of celebrating the 550th year of the great Guru’s birth, how he saw Truth and what view he took of it. In our callow age, we have all begun to speak glibly about ‘Post-truth’, and define it as ‘a philosophical and political concept’: something that all but hides the fact that we are referring to ‘the disappearance of shared objective standards for truth’, or to the “circuitous slippage between facts or alt-facts, knowledge, opinion, and belief’. From ‘Post-truth’ we might — tomorrow itself, not a long way away from now — graduate, or slide, into speaking, apart from ‘Half-truth’, of ‘Under-truth’, ‘Sideways-truth’, ‘Alternative-truth’, ‘About-to-become truth’. In stark contrast, what did Guru Nanak Dev believe in? “Sach pura na hovey naahin” are his words that rang out in the world. ‘Never, never ever, does Truth grow old’. For him it was the very foundation of all that is good and all that will survive: eternal, absolute, immutable, unalterable.

Also read:

Only Truth remains

Consider the number of times, and the manner, in which the great Guru spoke of Truth. Almost at the very beginning of the Adi Granth one finds these moving words of His which every devotee knows by heart and repeats: “Aad Sach; Jugaad Sach; Hai Bhi Sach, Nanak Hosi Bhi Sach.” In coarse translation: ‘In the beginning was Truth; in aeon after aeon, there was Truth. Truth is there, and — says Nanak — Truth is what will remain’.

At another place he rails bitterly at falsehood: “Kood nikhuttey Nanaka/ odak Sach rahai”, meaning, ‘Falsehood exhausts itself. In the end, Truth alone will prevail’. Again: “Sachahu urai sabhu key/upari Sach aachaar”. In other words, ‘Truth is the highest of all virtues/high, very high, is truthful living’. He speaks of Sach ki aag: Truth that is like Fire. Unremitting remains his emphasis: “Sach bina succha ko naahin,” he says: ‘Pure is only he who embraces Truth’. And he urged those who gathered around him and listened: “Kahai Nanak Sach dhyaiye/ suchi hovai ta Sach paiye”, meaning ‘Meditate but always on the True and the Eternal Lord who can be realised only when Truth occupies your heart.’ He knew what and where Sachkhand — the Realm of Truth, the Abode of Nirankar, the Formless — is.The Punjabi (and Hindi) word sach, derived from Sanskrit satya, exists clearly in another and shorter version: sat. And in that version, again through the great Guru’s luminous diction, one encounters it everywhere: Satnaam, at the very beginning of the great Mool Mantra, that the ‘Name’ is ‘True’; Satkartar is the True Maker; Satguru is evidently the True Guru; when we greet one another with Sat Sri Akal, or pronounce it aloud, what we are saying of course is that ‘True is the exalted Timeless One’.

Truth is what we are meant to recall through these words and names, for it is what permeates, activates, courses through, all that is good and all that will survive.

Best of all bargains

In the stories that have come down in the form of Janamsakhis — traditional hagiographic accounts of the life and career of Guru Nanak Dev as recorded or reconstructed by devoted followers, filled with encounters, parables, allegories, noble utterances — are clearly embedded references to what in his view Truth was and what the practice of it in daily life should be like. What was Sacha Sauda, for instance? Nanak’s father, Kalu Mehta, desperate as he was for his son to follow the ways of the world, decided once to ask him to ‘embrace a mercantile life’, and to this end instructed him to go to some far off place for buying salt, turmeric and other commodities for trading.

On the way, the episode goes, Nanak ran into a group of ‘holy men whose vows obliged them to remain naked in all seasons’. As narrated by Macauliffe who was basing himself on a Janamsakhi account, Nanak wanted to know the reason for their state only to learn that they had vowed to accept only such food and clothing “as was bestowed on them”. At which Nanak made up his mind to spend all his money on them — buying them food and clothing — for after all the money he had was meant to be spent “to the best advantage”, as per his father’s instructions. Wasn’t this the best of all bargains, he must have asked himself and others: a True Transaction, Sacha Sauda?

Fruits of honest labour

Truth and honesty, likewise, form the theme of another instructive episode: that involves a humble carpenter, Bhai Lalo, and an arrogant official named Malik Bhago. In the course of his travels from place to place, Guru Nanak, accompanied by his minstrel-companion, Mardana, visited Bhai Lalo who received them with great honour and, seating them in his humble kitchen, served them a simple meal. The Guru savoured the meal and ate it with relish. In the same place, around the same time, Malik Bhago threw a lavish feast to which large numbers were invited. Guru Nanak Dev declined the invitation first but was prevailed upon by people to go and partake of it.

Malik Bhago, already incensed by his invitation having been accepted with such reluctance, asked the Guru the reason that he had broken bread with the lowly carpenter but was averse to accepting his hospitality. Upon this, the episode continues, the Guru asked Malik Bhago for his share, and at the same time requested Lalo to bring him bread from his house. “When both viands arrived”, in Macauliffe’s words, “the Guru took Lalo’s coarse bread in his right hand and Malik Bhago’s dainty in his left, and squeezed them both. It is said that from Lalo’s bread there issued milk, and from Malik Bhago’s blood.” The meaning was clear: in Lalo’s bread there was Truth and honesty, for it had been earned by honest labour; and in Bhago’s there was little else than conceit and oppression, the blood of the exploited poor. This done, the great Guru got up and walked off, without saying a word.

The enlightenment

It is not as if before it all began, and the times before that, the great Guru knew it all, or that everything that was worth knowing had been revealed to him in its entirely. There is evidence of a seeking, of questions being asked. A ceaseless inquiry seems to inform his compositions. What is this all about? From where does it all come? Is there a Beginning? Where is the End? And so on.

One of the most celebrated, and mystifying, episodes that almost every Janamsakhi brings in, each in its own way, is about the Guru being lost to the world for a full three days. It relates to the stream called Kali Bein, and the forest close by. The Guru used to bathe in the river every morning to cleanse himself before meditating, and everyone was used to seeing him do it. Once, however, it so happened that the Guru went into the waters, or the forest nearby, and did not emerge. There was great consternation and panic set in: where is he, was the question on everyone’s lips. But he was not to be found. After full three days of search, everyone gave him up as lost, and sadness seized every heart. But then, suddenly, to the astonishment, and relief, of everyone, he emerged.

And, after emergence — enlightenment, as it has been called sometimes — the first thing that he pronounced in clear, loud voice, were the words: “Na ko Hindu, na Musalman” [‘There is no Hindu, no Musalman’].

It is as if he had struggled all these days, searching for the Truth, and found an answer to this strife-ridden world. One is reminded of the old shastric keeta-bhringa-nyaya: The Way of the Larva and the Butterfly. The description is beautiful: the larva stays, keeps sleeping as it were, in the chrysalis for a long time, as if preparing, and then, when the time is ripe, emerges from it, and takes to wing in the form of a butterfly.

What followed after that ringing statement is astonishing, as we all know. This because, boldly and firmly, a Truth had been discovered, and pronounced.

There is so much else, so may wondrous things, that the great Guru said, setting his own life up as an example. But how much do we take from it is the question. ‘Sach’? ‘Nothing but ‘sach’?

The writer is Professor Emeritus of Art History at Panjab University, Chandigarh