By rescheduling the foreign secretary-level talks, the government seems to have worked out that ‘drawing of red lines’ can be unsustainable

Observing the India-Pakistan relationship over the last two decades has been like watching a film where some of the actors change but the storyline remains hackneyed, predictable and stale. In a relationship that has been typically defined by déjà vu — the attempt at dialogue, the terror strike that is virtually written into the script, the standard condemnation and then the denials and the dithering — for the first time one can finally see a shift in approach.

AP FILENot once in all these years has Masood Azhar been probed for the hijacking of IC-814, which delivered him his freedom from an Indian prison in 1999. The sense of hope that was raised by the Pakistan media which reported his detention has already been belied

AP FILENot once in all these years has Masood Azhar been probed for the hijacking of IC-814, which delivered him his freedom from an Indian prison in 1999. The sense of hope that was raised by the Pakistan media which reported his detention has already been belied

At the Pakistan end, there has been none of the usual nay-saying. Instead, there has been a near-admission that the Jaish-e-Mohammed was responsible for the Pathankot air-base strike. On our side, India has wisely ignored the high-decibel pressure of television shows that believe the angry hashtag is War by other means. The biggest shift is in fact the move away from the needless histrionics we saw when the meeting of the two National Security Advisors in Delhi was cancelled over the Pakistanis wanting to meet with Kashmiri separatists. At the time an elaborate game of shadow-boxing reduced the diplomatic process to a ball-by-ball commentary on prime-time. Sushma Swaraj eventually saved the day and masterfully covered for the inconsistencies in the government’s approach with a pitch-perfect press conference. But by then the familiar and puerile melodrama of the India-Pakistan conundrum had done the damage.

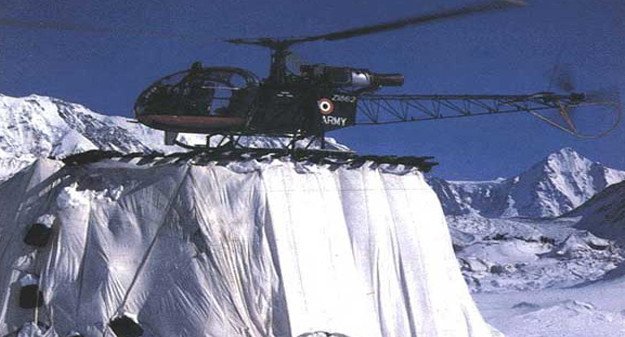

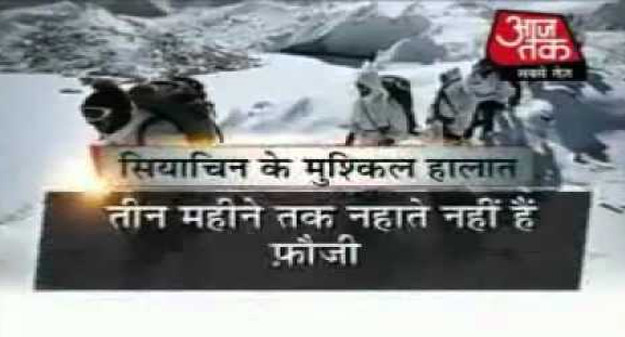

This time notwithstanding a much graver transgression — targeting an Indian military base is effectively an act of war — the hand at the wheel, on both sides, has been much steadier. Both countries have quietly agreed to reschedule the foreign secretary-level talks for another day in the near future, while the National Security Advisors continue to talk. This makes sense because the immediate aftermath of any terrorist violence is hardly the most opportune moment to talk about resuming the composite dialogue which would bring to the table a host of other issues, including the stand-offs over Sir Creek and the Siachen Glacier. The government seems to have finally worked out that the ‘drawing of red lines’ — a phrase we heard a lot of when the Pakistan-Hurriyat Conference nexus became the basis to scrap the NSA dialogue — may well have a nice, macho ring to it, but in the end it was quite simply unsustainable.

But despite the greater maturity there is still a big challenge that could yet trip the government’s next moves on Pakistan. By asking for “prompt and decisive action” against the perpetrators of Pathankot, the foreign ministry has created, and rightly so, the expectation among Indian citizens that the Pakistani probe must go well beyond ambiguous raids and non-specific crackdowns. Indian diplomats may well argue that long-term policy cannot hinge on an individual and that the future of talks cannot depend on whether Masood Azhar, in this case, or Hafiz Saeed (for 26/11) is put away or not. But there is already exasperation and cynicism among people at the fact that the terrorist responsible for the attack on India’s Parliament as well as the assault on the Jammu and Kashmir assembly has only been taken into ‘protective custody’. Not once in all these years has he been probed for the hijacking of IC-814 which delivered him his freedom from an Indian prison in 1999. The sense of hope that was raised by the Pakistan media which reported (it turns out incorrectly or at least prematurely) his detention has already been belied. Now imagine if four days before or after the foreign secretary’s arrival in Islamabad, Azhar is released from the house in Islamabad where he has been questioned. Such a scenario is entirely plausible after all he has never been formally charged with terrorism. Despite the government’s efforts to delink the next round of talks from Azhar’s arrest, the question will inevitably surface — with Azhar free, what precisely would qualify as the ‘definitive’ action India had

If it is true, as is often suggested, that the Jaish is not what the Lashkar is to the Pakistani military. The LeT has been used as a strategic weapon against India by Pakistan’s security agencies and the Jaish has on occasion turned on its own, most famously with the attempted assassination attempt on Pervez Musharraf — then the inability to put Azhar away or to even name him in press releases is inexplicable.

Let’s not forget that while the Jaish has been diminished today by counter-terror operations in Kashmir Valley it was Masood Azhar who was responsible for the very first suicide squad attack in Srinagar. Four months after he was freed in exchange for the passengers on board IC-814, a 17-year-old student and son of a teacher rammed a stolen car laden with explosives into the entry gate of the Army’s cantonment area in Badami Bagh. Azhar, who had recently launched Jaish-e-Mohammed (it did not exist before the IC-814 hijacking) and was now settled securely in Pakistan, claimed responsibility. Up until then the Lashkar-e-Taiba, by contrast did not endorse suicide because of strictures against it in Islam. Now the Jaish forced a shift in battle tactics. When the second suicide attack took place on Christmas that same year the Zarb-i-Momin — a mouthpiece for the Jaish called the 24-year-old bomber from Birmingham a “martyr”. So began the attempt to locate Kashmir within the larger global ‘jihad’ and try and transform a political insurgency into a religious one.

The Jaish may have gone off-script over the years but it has definitely been a part of the Pakistani Deep State’s Great Game in Kashmir. Acting against Azhar won’t be simple; no wonder a statement purportedly from the Jaish tauntingly declares that no arrest has happened.

Now, the difficulty for India is how to keep the process of engagement with Pakistan alive without seeming to renege on its own demand for “prompt and decisive action”. It’s a razor thin line that the Prime Minister must find the courage to walk on.

newsmaker

MAULANA MASOOD AZHAR Jaish chief

WITH MY KILLING, NEITHER WILL MY FRIENDS WILL MISS ME NOR WILL MY ENEMIES… AN ARMY WHICH LOVES DEATH HAS BEEN PREPARED… AS FOR MY FAMILY AND MY CHILDREN, THEY ARE TAKEN CARE OF BY ALMIGHTY ALLAH.

WHAT HE REALLY MEANT >

I HOPE NO ONE REMEMBERS THAT YEARS AGO, WHEN I WAS IN CUSTODY, I DID NOT DISPLAY ANY JIHADI QUALITIES. I HOPE THE ARMY THAT I HAVE PREPARED WILL BE THE CANNON FODDER WHILE I CONFINE MYSELF TO STIRRING QUOTES AND THREATS.

WHAT HE DEFINITELY DIDN’T >>

MY FAMILY IS BEING TAKEN CARE OF BY THE FRIENDLY FOLK IN RAWALPINDI WHO ARE NO DOUBT GUIDED BY ALMIGHTY ALLAH, BUT IF ANYONE ELSE WOULD LIKE TO CHIP IN, DO GET IN TOUCH THROUGH MY JIHADI FACEBOOK ACCOUNT.

CROSSOVER CONNECTIONS

The Indian and Chinese diasporas were shaped by the differences in their migration patterns

In the beginning, there was slavery. With its abolition, the British imperium constructed a globespanning system of labour movement. Coolies, both Indians and Chinese, were a product as were the Gujarati and Chettiar middlemen who helped ship their less fortunate countrymen around. Just feeding this system led to the creation of today’s rice bowls of the Irrawaddy and Mekong deltas. It also led to millions of Indians and Chinese migrants pouring into Southeast Asia during the 19th and early 20th century. Smaller numbers settled in each other’s countries. The story of this migration, the communities thus produced and cultural peculiarities that evolved, is the theme of this collection of academic essays.

The place where these two migratory flows found maximum confluence was the Malay peninsula. Between 1840 and 1940, eleven million Chinese settled there. They were joined by four million Indians. Indians came through a tightly controlled imperial contract system. The Chinese largely arrived to work in Chinese-owned enterprises. The Chinese were allowed more self-government and had more opportunities for social uplift. Mahatma Gandhi, on a visit to Singapore in 1908, noticed the gulf between the two. Contemporary observers found racial or cultural reasons for the disparity, but much of this book is about how circumstances — legal, political, economic and even historical accidents — shaped the future trajectory of, say, Indians in Burma or Chinese in Thailand.

The place where these two migratory flows found maximum confluence was the Malay peninsula. Between 1840 and 1940, eleven million Chinese settled there. They were joined by four million Indians. Indians came through a tightly controlled imperial contract system. The Chinese largely arrived to work in Chinese-owned enterprises. The Chinese were allowed more self-government and had more opportunities for social uplift. Mahatma Gandhi, on a visit to Singapore in 1908, noticed the gulf between the two. Contemporary observers found racial or cultural reasons for the disparity, but much of this book is about how circumstances — legal, political, economic and even historical accidents — shaped the future trajectory of, say, Indians in Burma or Chinese in Thailand.

Once they had finished their labour contracts, many Indian migrants in the colonial period did not stick around. “As much as 90 per cent of the Indians who went abroad in the colonial era eventually returned home,” writes Madhavi Thampi. Many Chinese who went overseas, however, were simply unable to return as their homeland disintegrated into civil war and then found stability in an oppressive one-party dictatorship. There are some excellent detailed studies on micro-issues like how the Chinese legal system treated its diaspora, why it’s a myth to talk of a trust-based and community-driven “Chinese capitalism” among its diaspora, and the almost comical problems British colonial judges had grappling with traditional Asian charitable concepts like ‘sinchew’ and the waqf.

Inevitably, given present geopolitical realities, there will be curiosity to know how Indians and Chinese compete or cooperate with each other when face-toface. On the one side there is the enthusiastic Chinese participation in Thaipusam celebrations by Singaporean Tamils or Kali-worshipping Chinese in Kolkata — in one case supposedly because a Chinese-Indian was granted a Canadian visa, after two rejections, after he prayed before the goddess. On the other is the persecution and harassment Chinese migrants faced at Indian hands during and after the 1962 war. Thousands were transported in guarded railcars to a concentration camp in Rajasthan in an episode most Indians have conveniently forgotten.

One essay describes how a tradition of Indian gold jewellery has slowly become Sinicized — in ownership, not design — in Singapore. Another describes the travails diaspora of both ethnicities have had in Myanmar thanks to the racism and xenophobia of the dominant Burmans. A new development are the thousands of Indians who have settled in Guangzhou to pursue “the China Dream”, often marrying locals, setting up flourishing businesses and all praise for Beijing’s leadership. Example: Sagnik Roy, an exchange student to China from Kolkata, who married a Chinese business professional and made $ 600 million fortune in pharma.

At times, one wishes deeper explanations were provided for the Indian and Chinese diaspora experiences. One study, comparing how local movies portrayed their respective migrant experiences, notes “Indian films depict Indians overseas as mainly living very affluent lives, and this element of struggle to achieve as depicted in Chinese films is hardly ever a factor in Indian ones.” How or why this interesting difference developed is never explained.

The governments of India and China also treat their diasporas differently. “Independent India took time to review its policies towards non-resident Indians… governments of republican China after 1911 found value in the overseas communities.” Both republican and communist China maintained large offices in their major cities to manage and strengthen family and locality bonds. New Delhi has only begun to awaken to the merits of its diaspora in the past decade — and largely only its most successful overseas brethren. Given that India inherited a welloiled migrant apparatus from the British while the Qing empire treated overseas Chinese as near-traitors, New Delhi’s seeming indifference deserved greater scrutiny. But in the authors’ defence it’s likely that a full account of two of the world’s largest and most successful ethnic migrants would fill a library — and their interactions an annexe.

The governments of India and China also treat their diasporas differently. “Independent India took time to review its policies towards non-resident Indians… governments of republican China after 1911 found value in the overseas communities.” Both republican and communist China maintained large offices in their major cities to manage and strengthen family and locality bonds. New Delhi has only begun to awaken to the merits of its diaspora in the past decade — and largely only its most successful overseas brethren. Given that India inherited a welloiled migrant apparatus from the British while the Qing empire treated overseas Chinese as near-traitors, New Delhi’s seeming indifference deserved greater scrutiny. But in the authors’ defence it’s likely that a full account of two of the world’s largest and most successful ethnic migrants would fill a library — and their interactions an annexe.