ONE hundred and forty years ago and six years after the British Raj fixed a 509 sq km Inner Line Reserve Forest in 1877, which sought to enclose a large part of what now constitutes Mizoram, the then Deputy Commissioner of Cachar reported in 1883 that four Lushai (Mizo) who ventured to tap rubber in this reserve were ‘shot down like birds’ on the pretext that they were ‘encroachers’.

The gay abandon with which this killing happened and was reported resonates powerfully in the wave of violence that Manipur has witnessed since May 3, when the state’s high-handed attempt to transform the Kuki-Zomi into ‘encroachers’ without following established procedures constitutes one of the major sources of structural violence against this community.

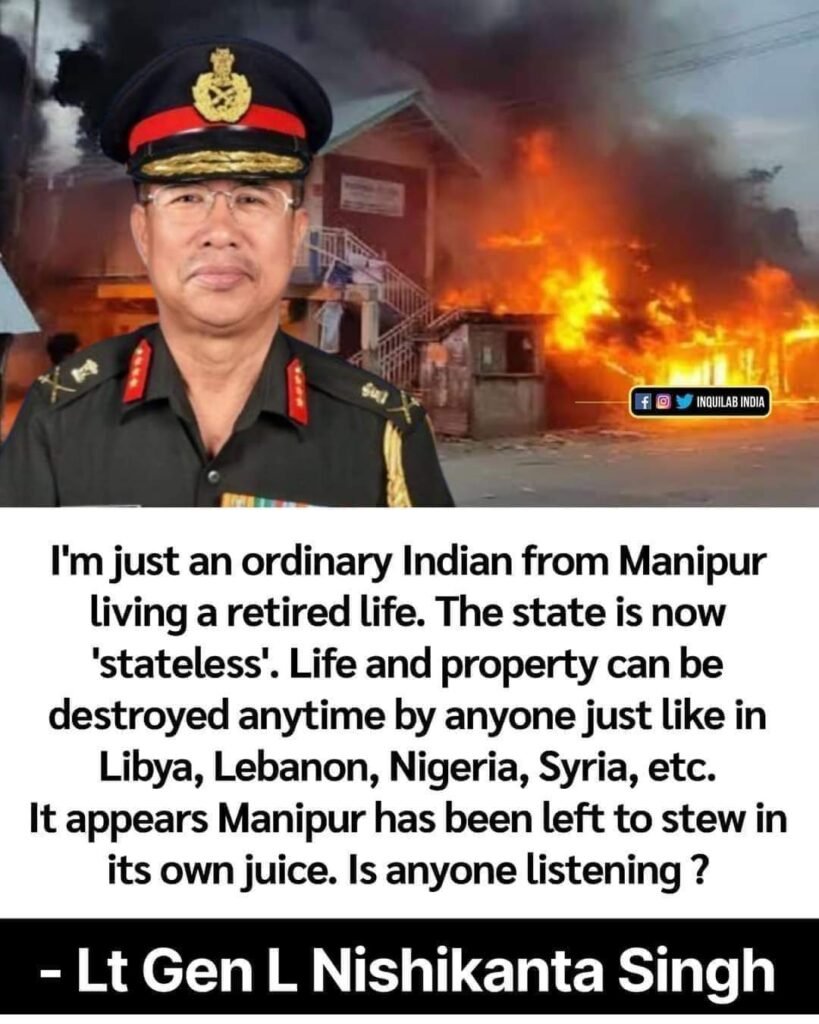

The deafening silence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for over 50 days and the refusal to impose the President’s rule to establish a semblance of law and order underscores the Centre’s abdication of constitutional responsibility. Not surprisingly, this continues to perpetuate structural violence against the Kuki-Zomi and allows Manipur to remain an island of lawlessness. Over 120 (including 94 Kuki-Zomi) lives have been lost, 355 churches and over 200 (including 160 Kuki-Zomi) villages burnt, and more than 50,000 (including over 41,000 Kuki-Zomi) have been displaced as a result.Advertisement

What is common in the 1883 killings and the current situation are the unilateral targeting of the Kuki-Zomi as ‘encroachers’ — and by implication, ‘troublemakers’ — and the high-handedness with which they were sought to be resolved by the colonial and post-colonial states. What is often ignored is a contextual understanding where hitherto owners and protectors of forest commons are sought to be transformed overtime into ‘encroachers’ by the state. The 1883 shooting emanated from the sidelines of modern state-making and state expansion that got fixated in a ‘territorial trap’ of fixing its border and in the enclosure of forest commons in an otherwise fluid and fuzzy land frontier; the current Manipur violence also stems largely from this, plus the high-handed manner in which the ‘protected forest’ (PF) concept has been sought to be implemented since October 2022.

On close scrutiny, you find that the Churachandpur-Khoupum PF, declared in 1966 under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, to cover some 38 villages spread across 500 sq km, was contested from the very outset. Not surprisingly, assistant settlement officers (ASOs) mandated by this Act reviewed the contestation and demand for the exclusion of these villages from 1971 to 1988. As many as 24 villages, spanning over 470 sq km, were excluded from the PF as a result.

However, Biren Singh’s BJP government, which began reviewing this matter in June 2022, nullified these exclusions in October 2022 on the pretext that the relevant ASOs did not conduct a proper inquiry before exclusions were made. At the heart of this is the contestation over uti possidetis juris, an internationally accepted legal principle which recognises the historical rights of actual owners of land and property.

Given that the state government does not have khas land (wasteland) in the tribal hill areas as the land belong to the tribal communities or village chiefs, and given that the hill areas are excluded from cadastral survey, the state is required to vet matters such as the declaration of certain areas under the PF to the village authorities, district councils and Hill Areas Committee (HAC), as mandated by law under Article 371C.

This point was underscored by the HAC in March 2021, when it resolved that the arbitrary extension of provisions of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, after 1972 without routing the matter to it, as mandated by law, would be null and void.

Instead of following the established procedure, Singh’s government came up with a set of satellite images covering a limited time space to bypass this and demonstrate that various new Kuki village settlements ‘encroached’ upon this PF. The eviction drive that it started on February 20 at Songjang village antagonised the Kuki-Zomi group. The refusal to regularise the tribal churches which possess dag chitha (paper document) — as against the 188 Meitei Hindu temples it has regularised since 2010 — and the eviction and demolition of three tribal churches in Imphal at night on April 11 in violation of the law — which mandated that no demolition be made before sunrise and after sunset — reinforced the high-handedness of the state.Advertisement

Meanwhile, various Meitei Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) were mobilised to support the eviction drive and a larger narrative was built to target Kuki-Zomi groups as ‘encroachers’, ‘illegal immigrants’, ‘poppy cultivators’ and ‘narco-terrorists’. This happened notwithstanding the fact that all communities are involved in poppy cultivation and drugs trade. Interestingly, out of the 2,438 drug traders caught during 2017-22, the Kuki-Chin, Meiteis and Pangals (Muslims) account for 33 per cent, 15 per cent and 43.5 per cent, respectively. Former police officer Thounaojam Brinda’s major drug expose in 2018, and Uripok MLA Raghumani Singh’s recent letter to Amit Shah demonstrate the direct involvement of high-ranking political leaders, who, in collusion with proscribed Meitei armed groups, control and play conduits to a larger international drugs-and-guns-trade network.

The centrality of land and the Meiteis’ grievances surrounding their lack of access to control tribal land and resources as the major source of Manipur’s violence must not be lost in the midst of the rancorous contestation. In the past, the discovery of tea, oil, rubber and coal since the 1840s in the North-East drove the state’s desire for territorial expansion and framing of a new land use policy in ways that augment the state’s revenue; in much the same way, the discovery in 2010 of a massive deposit of natural gas in the erstwhile Lamka (Churachandpur) district, which sits on the fertile Assam-Arakan basin, drives the state and majoritarian-minded Meitei CSOs to have direct control and access to resources in the tribal hill areas. The identification of 17 out the 32 natural gas fields in Lamka and Pherzawl districts by the Netherlands-based Jubilant Energy, which signed Petroleum Exploratory Licence with the Government of India in 2010, whipped up the desire of the integrationist state and majoritarian-minded Meitei CSOs.Advertisement

The Meiteis’ demand for Scheduled Tribe status, which gained momentum around this time, is seen by the tribals as a larger ploy to manipulate and bypass established procedures which protect tribal rights on land and resources. The choice for New Delhi is, therefore, stark: perpetuate structural violence against the Kuki-Zomi in gay abandon by projecting them as ‘troublemakers’, or invoke the political will to commit itself to upholding constitutional provisions to secure distinctive tribal rights and demand for a separate administration against the absolute autocracy of the majority.