Separate doctrines of the Army and the Air Force, and with each service doing its own training, are evidence that no amount of modernisation would help if the focus of the service chiefs remains on tactics. Success in war between India and Pakistan depends on the operational level of war.

Pravin Sawhney

Strategic Affairs Expert

SPEAKING at a recent seminar, the Air Force chief, Air Chief Marshal BS Dhanoa, while referring to the February 26/27 Balakot air spat, raised the critical war-winning issue. He said: “Did they (Pakistan Air Force) succeed in their objective? The answer is a clear ‘No’, as the attack was thwarted, while we achieved our objective in Balakot. This is the main argument.”

This is the wrong argument. If the Indian Air Force (IAF) had followed the correct argument, it would not have lost seven lives in the Mi-17V helicopter on the morning of February 27 when the air exchange was going on. Since the helicopter was not hit by Pakistani fire, it is reasonable to suspect that it went down by friendly fire.

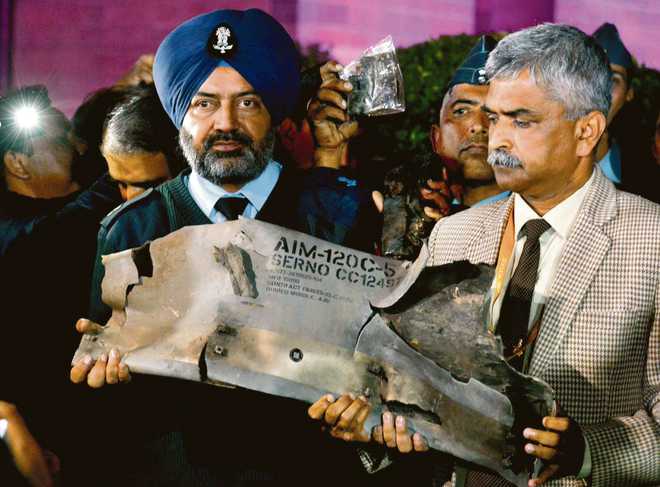

The correct argument is that the IAF breached Pakistan-controlled airspace on February 26 for hitting ‘non-military’ targets in Balakot. These were tactics (battle). The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) struck the next morning and also breached India-controlled airspace. This was done by the PAF in order to maintain balance at the operational (war-fighting or campaign) level of war. The operational level of war is where tactical battles in a particular area or theatre are given a coherent design and tackled as a whole. Moreover, since escalation was not the motive of the PAF either, it goes to its credit that they managed to miss military targets in the area which has extremely high density of Indian Army troops. Destruction of Indian Army installations would have compelled the Modi government to escalate, resulting in war, which neither side wanted.

The success in war between India and Pakistan depends on the operational level of war. A country can be successful at the operational level of war because of good higher defence management, firepower, joint training and mindset despite fewer numbers in terms of manpower and equipment, which is the case of the Pakistan military vis-à-vis the Indian one. Since air power, given its reach and flexibility, is central to success at the operational level, PAF’s quick retaliation was expected to maintain its air power credibility.

Yet, the IAF was not prepared for the inevitable. Had it been ready, the IAF would have seized control of airspace management after its February 26 strike, since it is its responsibility in war. The air corridors would have been marked and assigned, and all ground-based air defence networks (of the Air Force and Army) would have followed war protocols, waiting for the enemy’s counter-airstrike. Clearly, no one told the ill-fated helicopter not to take off on a routine peace-time flight, and the ground air defence observers, too, were caught on the wrong foot.

The issue, thus, is about tactics and operational level of war. The Pakistan military, learning from the Soviet Union, has always given importance to the operational level. This is why in the 1965 and 1971 wars, despite being more in bean-counting of assets, India never won in the western sector. Proof of this are the ceasefire line and the Line of Control, which otherwise would have been converted into international borders.

The situation, regrettably, remains the same today. Separate doctrines of the Army and the Air Force, and with each service doing its own training is evidence that no amount of modernisation would help if the focus of service chiefs remains on tactics. For example, after the Balakot operation, a senior Air Force officer told me that the PAF would not last more than six days. He believed in tactical linear success. What about the other kinetic and non-kinetic forces which impact at the operational level?

This is not all. Retired senior Air Force officers started chest-thumping about the Balakot airstrike having set the new normal. Some argued that air power need not be escalatory, while others made the case for the use of air power in counter-terror operations like the Army. Clearly, they all were talking tactics, not war. Had India retaliated to the PAF’s counter-strike, what it called an act of war, an escalation was assured. It is another matter that PM Narendra Modi had only bargained for the use of the IAF for electoral gains.

Talking of tactics, Air Chief Marshal Dhanoa spoke about relative technological superiority. Perhaps, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman would not have strayed into Pakistani airspace if his MiG-21 Bison had Software Defined Radio (SDR) and Operational Data Link (ODL). The SDR operates in the VHF, UHF, Ku and L bandwidths and is meant to remove voice clutter. The ODL provides the pilot with data or text, in this case from the ground controller. The officer, separated from his wing-man, and without necessary voice and data instructions, unwittingly breached the airspace and was captured by the Pakistan army. There are known critical shortages of force multipliers in addition to force levels in the IAF. Surely, the IAF Chief can’t do much except keep asking the government to fill the operational voids. But, he could avoid making exaggerated claims since his words would only feed the ultra-nationalists, and support the Modi government’s spurious argument of having paid special attention to national security.

The same is the case with Rafale and S-400. These would certainly help, but would not tilt the operational level balance in India’s favour. For example, the IAF intends to use S-400 in the ‘offensive air defence’ role rather than its designed role of protecting high-value targets like Delhi, for which it was originally proposed. For the protection of high-value targets, the Air Headquarters has made a strong case to purchase the United States’ National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS). This is ironic, because while S-400 can destroy hostile ballistic missiles, NASAMS can’t do so. It can only kill cruise missiles and other aerial platforms. The thinking at the Air Headquarters is that since there is no understanding on the use of ballistic missiles — especially with Pakistan — both sides are likely to avoid the use of ballistic missiles with conventional warheads lest they are misread and lead to a nuclear accident. So, NASAMS may probably never be called upon to take on ballistic missiles.

Given the direction of the relationship between the India and Pakistan, this assumption may not be the best to make when procuring prohibitively expensive high-value assets.