t is not necessary to denigrate Nehru to admire Sardar Patel

Vappala Balachandran

Ex-special secy, cabinet secretariat

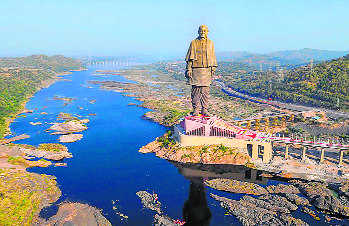

A recent report that the next meet of our foreign missions’ heads would be held ‘under the shadow’ of the towering Sardar Patel statue is welcome news. The occasion will allow refocus on that great man, the architect of Indian unity. The title ‘Indian Bismarck’ does no justice to him. It took nine years (1862-71) for Bismarck to achieve German unification after waging three major wars. Patel secured peaceful unification of the huge Indian landmass, including integration of most of our 562 princely states, within two months of the June 3, 1947, Cabinet Mission Plan. No other person has achieved this in world history.

The ongoing inquisitorial hypothesis on whether Patel would have faced India’s early security challenges better than Nehru as Prime Minister would be meaningless unless we juxtapose such propositions against our systemic framework existing in the relevant period. Unless this is done, such discourses would do no justice to both leaders who, despite their strategy differences, worked with great affection to each other.

China and Pakistan were our biggest challenges in 1947. They continue to be so even now. An unremitting contention is whether an expansionist China could have been contained more firmly by Nehru after receiving Patel’s long letter of November 7, 1950, about Tibet. By then the intention of the new Communist government that it would reclaim the Qing-era boundaries was known all over the world. This was also after the Battles of Dengke (June 1950) and Chamdo (October 6-19, 1950) to force the Dalai Lama to accept Chinese rule.

The story of a resurgent and combative China starts in 1919 when signs of a ‘helpless, hopeless, and inert mass of China’ (Lord Curzon) coming alive and exploding were visible. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles, dominated by the big powers, handed over the old German interests in China, including Shantung Peninsula (Cradle of Chinese civilisation, birthplace of Confucius) to Japan. The leadership for the scorching May 4, 1919, ‘anti-imperialist, cultural & political movement’ passed on to the Communists to evict Russians, British, French, Germans and Japanese from their territory. From 1949, China’s quest was to reclaim all its ‘lost territories’.

Praise for the PLA’s prowess came from an unexpected quarter. Barbara Tuchman, biographer of Gen Joseph Stilwell, says that the General had a ‘notable impression’ of the PLA during the Communist resistance of Japan in Shansi (1936). Stilwell was sent by President Roosevelt to help Chiang Kai-shek during World War II. The same impression emerges if we study their tactics during the 1950 Korean War when they deployed 1.3 million ‘volunteers’ who were PLA troops to help North Korea when the UN forces (90% American) crossed the 38th parallel on September 25, 1950. They beat back the best army in the world, pushing them back beyond the 38th parallel. They risked losing 6 lakh lives only because they feared that US would invade their mainland.

The declassified ‘Top Secret-Eyes only’ White House memorandum on the Nixon-Zhou Enlai meeting on February 23, 1972, also confirms this fear. Zhou alleged that the 1962 incident actually started in 1959 when Khrushchev “tore up the nuclear agreement between China & Soviet Union” and instigated India to attack China. In 1959, it was in Ak-Sai-Chin, Western Sinkiang. The 1962 incident in which India crossed the McMahon Line into Chinese territory was when Russia told Nehru that “China would not retaliate against them”. “So we had no choice but to drive him out.” Zhou told Nixon that Nehru had expansionist ambitions when he wrote Discovery of India.

Nehru wrote a long reply to Patel on November 18, 1950, agreeing with him on the Chinese threat but suggesting that the military build-up simultaneously on the Western and Northern fronts would “cast an intolerable burden on us, financial or otherwise.” He recommended a diplomatic approach to seek “some kind of understanding with China” while preparing for all contingencies.

On Pakistan and Kashmir, it is very difficult to assess what exactly was in Patel’s mind. His closest aide, VP Menon, had mentioned that Lord Mountbatten, during his visit to Kashmir (June 18-23, 1947) had told Maharaja Hari Singh that “if he acceded to Pakistan, India would not take it amiss and that he had the firm assurance on this from Sardar Patel himself.” Mountbatten’s ‘Report on the Last Viceroyalty’ (March 22-August 15, 1947), published in 1948, confirms this. This has been more or less confirmed by Balraj Krishna, Patel’s biographer, quoting MR Masani that Patel had told him that he “could settle the Kashmir issue in no time by arranging that the Kashmir Valley should go to Pakistan and East Pakistan to India.”

Krishna has also reproduced a letter from the then Indian Air Force Chief, Air Marshal Sir Thomas Elmhirst, who was also holding the charge of Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee, that he remembered Patel telling him that he would be in favour of a full-scale war with Pakistan, “if at all the decisions rested on me” to “settle down as a united continent”.

The problem is arriving at any historiographical judgment only on private opinion without considering whether such action was legally possible in 1947. India was still a dominion under the Governor General to represent the British Crown till it became a republic in 1950. His assent was necessary under Section 5 read with 9 of the India Independence Act (IIA), 1947, for all purposes, including deployment of armed forces. Also, the Indian Army was under British command till January 1949. On the other hand, Patel had participated in all crucial meetings chaired by Mountbatten and also agreed with all decisions.

The moral of the story is clear: it is not necessary to denigrate Nehru to admire Patel. We owe our freedom and stability to the triumvirate of Gandhi, Patel and Nehru. Each one was indispensable to our nation.