Guru Nanak’s bani enables us to know the spiritual and moral reformation he brought about in his lifetime

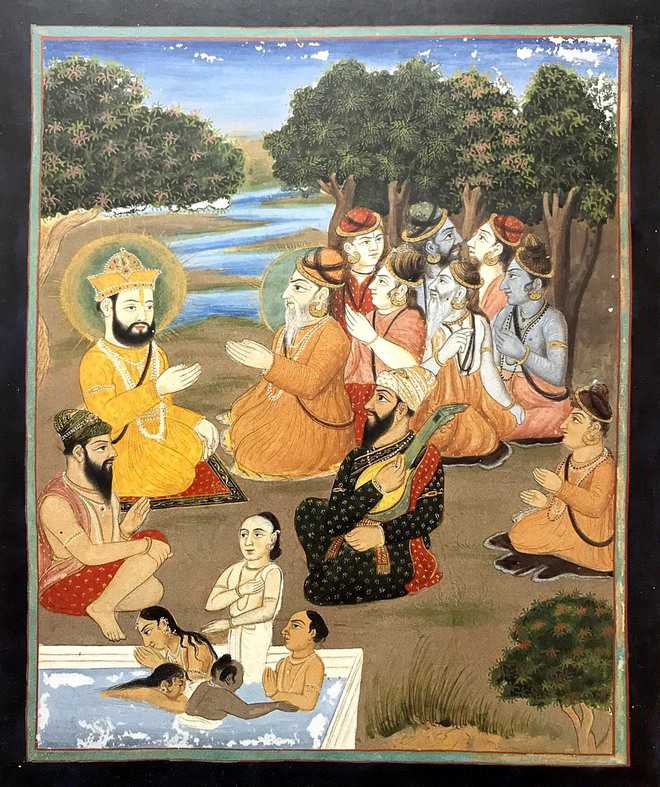

Guru Nanak addresses jogis at Achal Batala — from the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (ca. 1800-1850)

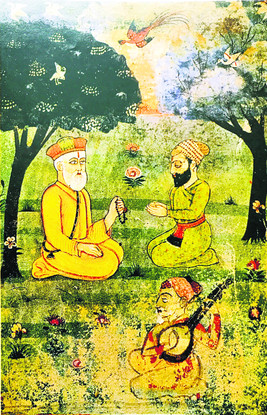

Baba Nanak, Guru Angad and Mardana — B-40 Janamsakhi (1733)

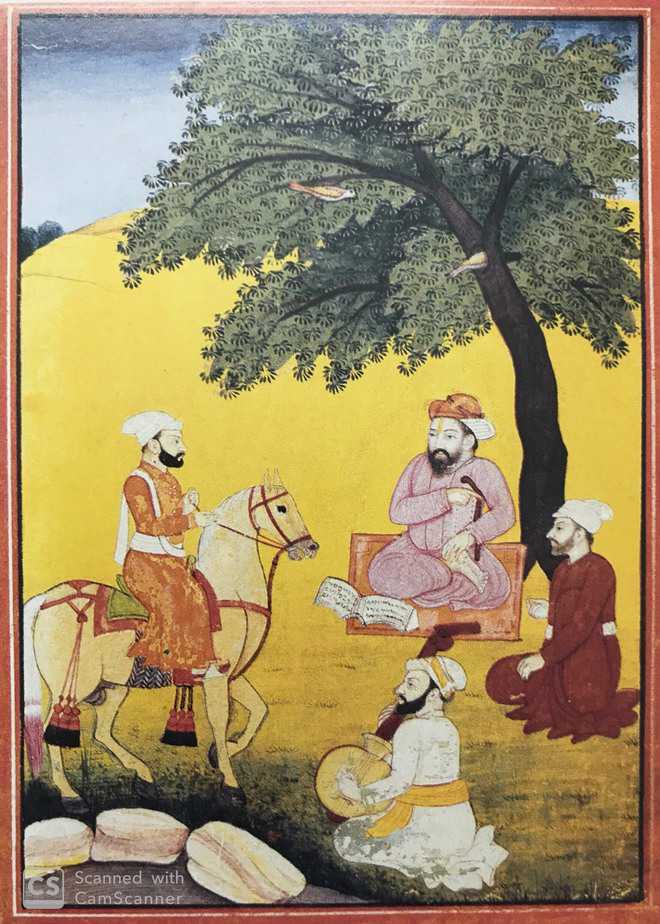

A king pays homage to Guru Nanak — from Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh (ca. last quarter of the 18th century)

J.S. Grewal

In a well-known 20th-century portrait, Guru Nanak is sitting in meditation with his eyes closed. In his compositions (bani) though, Guru Nanak keeps his eyes wide open. He says in fact that he had seen all nine regions (nav-khand) of the earth, and seen sacred places, markets and cities, walking, as it were, on his eyes. The range of his comments is exceptionally wide, covering the social, political, and religious aspects of the life of his contemporaries. His bani enables us to know the kind of socio-cultural regeneration he brought about in his lifetime.

Contemporary social order

Guru Nanak was thoroughly familiar with the social order of his time. The royalty, the nobility, the officials of the government, its intermediaries at lower rungs, and common people figure frequently in his compositions. Apart from the mulla and the qazi, the shaikh and the pir, several professions and occupations are noticed. Guru Nanak underscores the life of luxury of the ruling class and the grinding misery and ignorance of the rai’yat, the subject people. He takes notice of the ideal of the four varnas, and the outcastes. High caste has no merit in his eyes. The people who forget God have no caste.

The Sikh of the Guru is expected to rise above the distinctions of caste. Equality between men and women is emphasised in many verses of Guru Nanak. The spiritual and ethical message for women is exactly the same as for men. There is no doubt that this liberation (state of union with God) was made accessible to women. The sada-suhagan enjoys the love of her spouse (God) throughout her life. However, she is placed in the patriarchal family which was inegalitarian. The tension between equality in the spiritual realm and inequality in the social domain was not easy to resolve.

Guru Nanak saw no merit in ritualistic practices. The sacred thread in his eyes has no spiritual or moral efficacy. The thread of the Brahmin does not restrain him from scandalous conduct. There is no restraint on his feet, his hands, his tongue, and his eyes. The sacred thread of the Khatris did not stop them from pandering to the rulers whom they regarded as unclean (mlechh). They wielded the butcher’s knife against the people on behalf of the rulers.

Similarly, the meticulously observed chauka was useless. They told others to keep away but the line drawn around did not keep out their own ignorance and hardness of heart. The notion of purity and impurity (sutak) was merely an illusion. It had nothing to do with ethical living. To regard women as impure during childbirth or menstruation was sheer ignorance. There can be no reproduction without women, and there would be no humanity without reproduction.

Guru Nanak ridiculed the popular practice of floating lighted lamps in water for the dead as an obituary rite. Another such rite was the performing of shradhs in which food was offered to Brahmins to eat on behalf of the dead ancestors of the patron. The dead received nothing. Guru Nanak’s social comment extends to the rites of passage. They who mourn the death of a dear one forget that they themselves would die. Formal mourning served no good purpose. The debate about the mode of the disposal of the dead was futile. Only God knows what would happen to anyone after death.

On the whole, the social order at the time of Guru Nanak was marked by discrimination on the basis of caste and gender, and by ritualistic practices.

Polity and politics

There is explicit reference to the rule of Muslim Pathans (Turk-Pathani ’aml). The name of God now is Allah and the favourite colour is blue. An assessment is built into the association of Muslim rule with the Kaliyuga, the worst of the cosmic ages. Human beings had turned into goblins. Greed was now the Raja; and lust was the Sikdar (shiqdar), local administrator. The seed was crushed, and it could not sprout.

The wielders of power come in for severe criticism. Millions may stand up to salute the masters of vast armies, and millions may obey them, but all this is futile without honour in God’s court. Unlike the ordinary people, the rulers collect wealth with the levers of power, and their thirst for power is never quenched. Indeed, the rulers are butchers; they suck human blood. Justice is administered not in the name of God (as the primary duty of the rulers) but only when the palm is greased. There is discrimination on the basis of religious affiliation. ‘Now that the turn of the shaikhs has come, Ad Purkh is called Allah; it has become customary to tax gods and their temples.’

The verses of Guru Nanak, known as Babur-bani, refer to Babur’s invasions. The army of Babur is called the marriage party of sin; brides are demanded by force; the rite of marriage is performed by Satan. The reference here is to rape. The Mughals descended as the agency of death; the people cried in suffering. If the mighty strike the mighty, the fight is equal. But if a lion falls upon a herd of cattle, God is accountable. Actually, Guru Nanak is questioning God. Many unarmed civilians were killed, and the rulers of the land failed to protect them. Thus, both the Mughals and the Afghans stand indicted.

The Afghans suffered for their political and moral failure. Gone were their sports and stables, and their sword-belts and red tunics. Their tall mansions were razed to the ground and the princes cut into pieces. God takes away the goodness from those whom he wishes to mislead. The women of the ruling classes were dishonoured. Had they thought beforehand, they would not have suffered. There is a moral dimension to a political situation in which men and women suffer because of their misdeeds.

With all their power, wealth and pride, the rulers remained subject to the power of God. His service was far preferable to the service of earthly rulers. He who has access to the divine court does not have to bow to anyone else. This statement carries the implication of potential defiance. Indeed, Guru Nanak talks of the possibility of the white cloth being dyed and of the split seed becoming whole to sprout again. In other words, spiritual and moral regeneration could become the means of social regeneration.

Primacy of liberation

It is important to note that Guru Nanak gives primacy to liberation, the supreme purpose. Earthly pursuits have no meaning if God is forgotten or ignored. The foremost duty of a human being is to dedicate his or her life to God in order to become one with Him and to be released from the cycle of death and rebirth. The path of liberation is hard to follow, like walking on the sharp edge of a sword. It is important to point out that worldly life is not to be renounced but transformed.

Guru Nanak talks of maya, mamta and haumai as the great obstacles on the path of liberation. The thirst for maya is never slaked. Affection for kith and kin (mamta) is more difficult to overcome. Above all, human beings remain preoccupied with themselves, suffering from the disease of self-centredness (haumai). Guru Nanak offers loving devotion to God as the antidote for maya, mamta, and haumai. Loving devotion to God was not divorced from bhay or bhau (reverential fear due to the realisation of God’s power and grace). This way of bhagti was found through the Guru and with God’s grace.

Guru Nanak lays great emphasis on action (karni), rather than verbal profession (kathni). The familiar proverb ‘you reap as you sow’ occurs at many places in Gurbani. Everything is lower than the realisation of truth but truthful living is higher. The world is the stage where merit is earned through altruistic action (seva). To help others is to serve God. Parupkar is a part of God’s raza. The Guru, too, is Parupkari. The Sikh who lives in accordance with God’s raza is the king of kings.

The state of liberation is also called nirban-pad or pad-nirbani, the state of detachment. This state is everlasting (amrapad). There is no haumai in the state of liberation, and there is no fear. It is a state of bliss and peace. The liberated-in-life remains committed to social obligations with a spirit of detachment with a larger concern for the welfare of others.

Contemporary religious traditions

Guru Nanak makes a good deal of comment on the religious beliefs and practices of his contemporaries. He talks of the representatives of three traditions: the Brahmanical, the ascetical, and the Islamic. His comments on the Brahmanical traditions (Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Shakta) include scriptures, gods and goddesses, worship of idols, rituals, charity, pilgrimage to sacred places, and dance and dramatic performances. Guru Nanak looks upon Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh as God’s creatures. They are not everlasting.

Contrary to the general impression, Guru Nanak is also critical of worship of Rama and Krishna. In the first place, there is no room for incarnation in Guru Nanak’s conception of God. There is no spiritual or moral merit in dramatic representations of Rama and Krishna. Guru Nanak tells the Vaishnavas that the adoration of God is the real dance; all else is sensual pleasure. Guru Nanak has little appreciation for the Gorakhnathi Jogis. He tells them to have contentment as their earrings, productive work as their begging bowl, meditation of God as the ash on their body, the fear of death as their cloak, trust in God as their staff, and keeping their body free from evil as their skill. To regard all human beings as equal is to belong to the highest order of the jogis. There is no ethical merit in possessing supernatural power. Only he can be called a real jogi who regards all human beings as equal. The real avadhut remains hopeless-in-hope (asa mahi niras). The gulf between the Jain monks and Guru Nanak was the widest. Apart from their asceticism, renunciation, and mendicancy, they are denounced for their atheism.

The Muslim claim to an exclusive possession of true faith had no justification. God does not consult anyone when He creates or destroys, when He gives or takes away. There is a suggestion in a verse that Guru Nanak appreciates the way of the Sufis. ‘It is not easy to be a Mussalman; one should be called so if one is a real Mussalman’. First of all he should adopt the path of the auliya. However, Guru Nanak did not appreciate certain practices of the Sufis. They accepted patronage from the state in the form of revenue-free land, going against their own ideal of complete trust in God. Guru Nanak denounced the practice of the Sufi shaikhs to bestow caps (kulhan) upon their disciples and to authorise them to guide others. This appeared to be presumptuous on the part of the Sufi shaikhs.

God, Guru and shabad

Guru Nanak’s religious thought is uncompromisingly monotheistic. There is one God, and no other. He is self-existent; He never dies and He is never born. He alone is active (karta). He is devoid of fear and enmity. As the only eternal entity, God is equated with Truth. In Guru Nanak’s conception of God, the attributes of power and grace are two sides of the same coin.

The concepts of hukam and nadar flow from these attributes. His command (hukam) keeps the physical universe and the moral world in order. His grace enables human beings to do what He likes; they act in accordance with his hukam, and become acceptable to God.

The Guru, in the first place, is God himself. He has revealed Himself in his creation. He who appropriates the Guru’s Word is liberated and he can liberate others. The Guru is found in the sant sabha. The true Guru is found in sat-sangat where God’s praises are sung through the shabad. The mind is turned to God only by praising Him through the Guru’s shabad. The true Guru enables one to meet God. With the true Guru as a friend, one receives truth and honour in the divine court.

The term shabad occurs frequently in the compositions of Guru Nanak. It refers to the self-revelation of God. But more frequently it refers to the bani of Guru Nanak. There is no understanding without the shabad. God is praised through the Guru’s shabad. The woman who gets rid of self and adorns herself with the Guru’s shabad finds the spouse in the home. All illusion is removed by the pure bani. The shabad leads to recognition of the true creator. The Gurmukh is attached to the truth through the shabad and sees God everywhere. The one without any sign, colour or shadow is recognised through the shabad. True is the Guru’s shabad that leads to liberation. There is only one shabad, and it is recognised through the perfect Guru. All nads and Vedas are in Gurbani.

The compositions of Guru Nanak are an integral part of divine revelation. He was called, as he says, by God to his court and given the robe of true adoration with the nectar of the true Name. They who taste it through the Guru’s instruction attain peace. The minstrel (dhadi) of God spreads the message of the shabad. He utters the divine bani as commanded by the Lord. This claim carries the implication that Guru Nanak’s message was more authoritative than any known scripture.

The Sikh Panth

Critical of the socially privileged in society, Guru Nanak aligned himself with the lowest of the low. Critical of the rulers and the ruling class, he sympathised with the subject people. Marked by moral degradation, ritualistic practices, discrimination, oppression and injustice, the social order needed regeneration. The means of social regeneration for Guru Nanak was his own ideology. At the centre of the universe is God. He created the universe through his hukam and keeps it in order. God’s hukam and nadar transcend the law of karma. God Himself is the guide to liberation. His creation is His Word (shabad). As the source of guidance, shabad is the Guru. The divinely inspired bani of Guru Nanak is a part of revelation. Shabad and bani stand equated.

Social action is necessary for liberation, and it becomes all the more important for the liberated-in-life. He remains active in society, not in his own interest so much as in the interest of others. The most important function of the liberated-in-life is par-upkar, that is, all kinds of service for others as human beings. No distinction, whatsoever, is made between one human being and another for the purpose of redemption. The path chosen by Guru Nanak was open to all.

The panth founded by Guru Nanak was based on egalitarian ideology. The Sikh of the Guru had a distinct place of worship, called dharamsal (later gurdwara). They worshipped God in congregation regardless of caste or religious background of the participant. The bani of Guru Nanak was used for kirtan and katha. Ardas (supplication) was an essential part of worship. All the Sikhs ate together from a common kitchen (langar). This was the legacy Guru Nanak left for a successor to carry forward, installing him as the Guru in his lifetime. Guru Nanak discovered a new path and founded a new panth, as an instrument of universal redemption.

— The writer is a historian and former Vice-Chancellor of Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar