‘Wanted’ posters of PM Modi, Amit Shah displayed at Khalsa Parade in Surrey

As advance polling for Canada’s federal elections concludes on Monday, leading up to the final voting day on April 28, a series of unsettling incidents within the past 24 hours has spotlighted the delicate tensions simmering within the Indian diaspora and Indo-Canada relations.

The vandalism of a gurdwara and a Hindu temple in Surrey on Saturday—allegedly by pro-Khalistan activists—alongside the emergence of anti-India and anti-Hindu slogans at the Khalsa Parade in Surrey later in the day, starkly underline these frictions. Adding to the charged atmosphere, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre’s Saturday visit to Brampton’s Guru Nanak Mission Centre (GGNMC) has drawn attention to the complex interplay of cultural, religious, and political dynamics within the communities.

The vandalisation of the gurdwara and the temple with pro-Khalistan and anti-India graffiti coincided with the Khalsa Parade, where “wanted” posters of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Home Minister Amit Shah and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar were paraded. While this has attracted significant criticism, it speaks volumes about the simmering tensions and attempts to polarise communities. Social media is teeming with videos showing pro-Khalistan activists, with flags, asking Indians (read Hindus) to “go back to their country”.

Mocha Bezirgan (@BezirganMocha), who describes himself as an “anti-corruption and anti-terrorism investigative journalist”, wrote on X: “Happening now: World’s largest Khalsa Day Parade in Surrey, B.C. Chants of ‘Kill Modi Politics’ echo throughout the parade route, accompanied by Sikh hymns and martial arts demonstrations…”

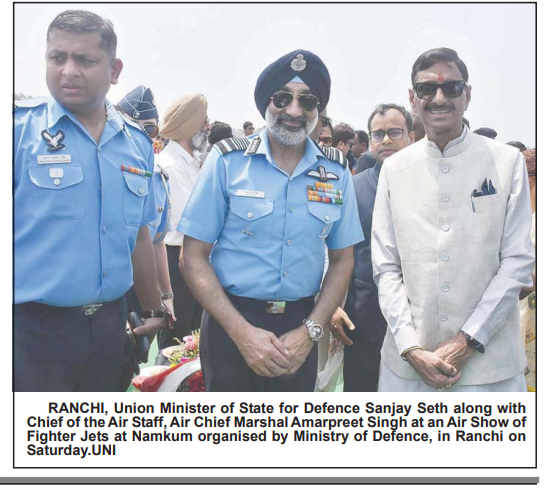

The event attracted politicians of all shades, with Conservative and NDP leaders Poilievre and Jagmeet Singh attending in person. Liberal leader Mark Carney was notably absent. The event saw participation from over 5,50,000 people, and many have criticised the open display of Khalistani and anti-India sentiments amidst the glorification of the alleged Air India bombing mastermind.

Ahead of the Khalsa Parade, the Indian diaspora in Canada awoke to the news of vandalisation of the gurdwara and the temple in Surrey with hate graffiti. While both incidents are under police investigation, the Khalsa Diwan Society, which runs the gurdwara, blamed the vandalism on a small group of Sikh separatists advocating for Khalistan. “This act is part of an ongoing campaign by extremist forces that seek to instil fear and division within the Canadian Sikh community. Their actions undermine the values of inclusivity, respect, and mutual support that are foundational to both Sikhism and Canadian society,” the statement said. Incidentally, the management of this gurdwara promotes Sikh-Hindu unity and has kept Khalistani ideologues at bay.

Around 3 am., Lakshmi Mandir in Surrey was also vandalised with the same kind of graffiti. According to reports, CCTV footage with the temple management shows two men vandalising the walls. This was the third time the temple had been vandalised.

Daniel Bordman (@DanielBordmanOG), a journalist, wrote on X: “I went to the Lakshmi Mandir in Surrey that was vandalized last night by Khalistanis. This is the third time it has been vandalized. I spoke to management and the devotees, and they do not feel like the police or the political establishment cares at all.”

Poilievre’s Saturday visit to Brampton’s GGNMC has also sparked controversy as this centre is viewed to be pro-Khalistani, having dubbed Nijjar a “martyr”. Poilievre was accompanied by his close but controversial associate, MP Tim Uppal. Tim’s wife is said to be associated with the World Sikh Organisation, and his brother, Raymanpreet Singh Uppal, was charged in 2014 but later acquitted in a drug case.

While these incidents have undoubtedly shaken communities, it is crucial to recognise the broader context in which they occur. The Sikh diaspora in Canada is diverse, with a vast majority dedicated to peaceful co-existence, cultural preservation, and community development. The actions of a few hardliners must not weaken multicultural ties.

Irrespective of who wins the polls, it’s imperative that political leaders must take a stand on these sensitive issues and ensure that the rhetoric does not exacerbate these divisions. The focus should remain on unity, mutual respect, and the democratic principles that define Canada.