While the infiltrators couldn’t implement what they had set out to do, 4 brave officers including Major Kaustubh lost their lives in the process of stopping them.

Talking to Mirror Now, Kanika said that it was her husband who taught her to face life’s challenges boldly.

Kaustubh used to say that if life pushes you down, you always have the harness to pull yourself back.

Don’t let people game the system, deal with tax evaders firmly” is what the finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, supposedly told the income tax department on July 25, soon after she presented the Union Budget in Parliament. The finance minister has set a lofty target of a 23.3% increase in income tax revenues for financial year 2020, compared to a meagre 7% growth in the current year. In other words, Sitharaman wants income tax revenues for the next year to grow three times faster than it did this year. Hence, the putative pep talk to income tax officers.

AFP■ The purported suicide note of VG Siddhartha is a grim reminder of the devastating impact that an aggressive tax revenue targeting policy can unleash on our economy and societyThe premise behind this policy goal is flawed, and disturbing. The tone and tenor of the finance minister’s budget this year is symptomatic of a larger and deeper malaise of a “morality governance” paradigm that is threatening to derail our society and economy, as seen in the recent tragic suicide of the founder of the successful Café Coffee Day business, VG Siddhartha.

There is a “good versus evil” framework that defines economic policymaking of the Narendra Modi government. The playbook seems to be to portray an “evil”, then position oneself or a policy as the “good”, to kill and triumph over this “evil”.

It started with the demonetisation policy in November 2016 that constructed a false narrative of an “evil” of millions of Indians, hoarding illegal cash in their homes, and under their

pillows. The PM’s demonetisation idea was supposed to be the “good” that will destroy and triumph over this “evil” of black money hoarders. It did not matter to the government that evidence pointed to the fact that hoarded black money was typically not stored in cash. It did not also matter that eliminating 86% of all currency was bound to impact hundreds of millions of innocent others who did not possess any black money. All that mattered was the popular narrative that the government was fighting a “good versus evil” battle.

Similarly, the fundamental economic idea behind the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was to ease bottlenecks for inter-state trade and boost commerce. Instead, the Modi government once again applied its morality governance paradigm, and turned GST into a narrative of the “good” (GST) that will destroy and triumph over the “evil” of informal businesses that remain outside the tax net. The GST initiative was recast as a policy aimed at demolishing the evil informal businesses that evaded taxes, and formalise them into the mainstream economy. Again, it did not matter to the government that economic history tells us that no major country has set out to explicitly formalise its economy as a stated goal, and formalisation is an inevitable outcome of economic development. The net result of this was a botched-up GST, with a messy structure and harassment of small businesses, portrayed as the villains. This crushed the economy, which is still reeling under these twin shocks of demonetisation and a messy GST.

The latest in this playbook is the underlying tone of the recent budget presented by Sitharaman. The prevalent notion that India has a vast population of tax evaders is unfounded and baseless. Individuals earning less than ₹5 lakh a year need not pay income tax, as per the latest income tax slabs and exemptions. Going by India’s income distribution, less than 10% earn more than ~5 lakh a year. In other words, 90% of Indians are anyway legally exempt from having to pay income tax. India’s income tax exemption limit for its level of per capita Gross Domestic Product is among the highest in the world, and it is one big reason why the percentage of Indians that pay income taxes is very low. While there surely are income tax evaders, it is not the case that a vast majority of Indians evade tax, and need to be dealt with “firmly”, as it is made out to be.

But in the morality governance paradigm of this government, there is this big “evil” of hundreds of millions of tax evaders, and the government is apparently fighting this evil through aggressive tax scrutiny and collections. Like demonetisation and GST, this belligerent tax collection policy is fundamentally flawed in its premise. At a time when business confidence is low, the finance minister’s license to the income tax department to go after imaginary tax evaders, and extort sacks of tax revenues, will paralyse business activity and destabilise the economy even further. The purported suicide note of Siddhartha, alluding to the pressure he faced from the income tax department, is a grim reminder of the devastating impact that an aggressive tax revenue targeting policy can unleash on our economy and society.

Ostensibly, commentators may argue that this morality governance paradigm of portraying the PM and his government as the “good” triumphing over the “evil” of the nation has reaped rich electoral dividends for the ruling party, regardless of its economic consequences. Electoral victories aside, I hope that the Modi government will also appreciate that economic policy for our nearly $3 trillion economy needs careful thought and analysis, and cannot be based on some whimsical “hero versus villain” or “good versus evil” morality storytelling.

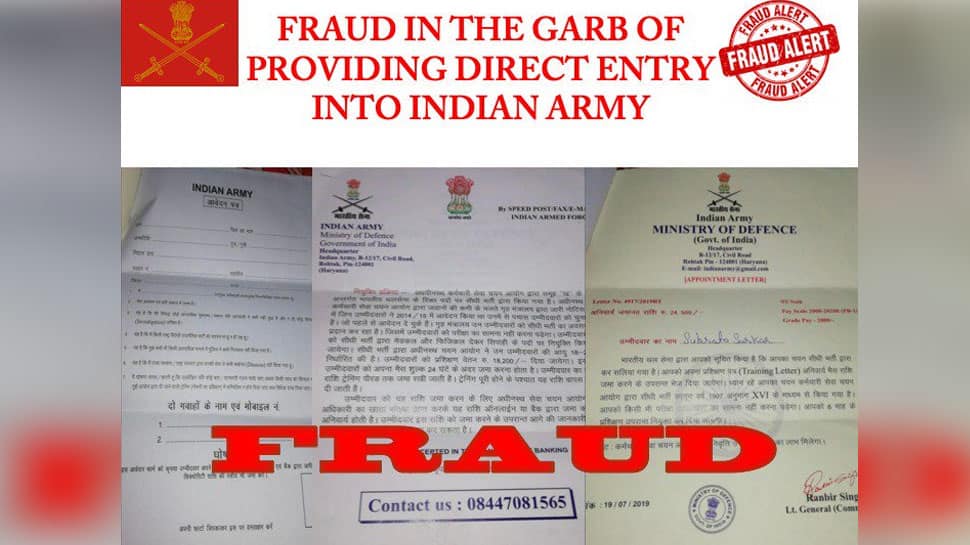

Taking to Twitter, the Army said, “Number of fraudsters are using fake Indian Army letters claiming to be providing direct entry into Indian Army. Some reported to have been duped. Be Careful! Do not fall for such deceit & trap.”

The Army on Wednesday issued a warning to the people against fraudsters who are using fake letters claiming to provide direct entry into the Indian Army. Some people have also been, according to the Army. The Army has asked people to be careful and not fall for such trap and deceit.Taking to Twitter, the Army said, “Number of fraudsters are using fake Indian Army letters claiming to be providing direct entry into Indian Army. Some reported to have been duped. Be Careful! Do not fall for such deceit & trap.”

G Parthasarathy

Former diplomat

It now is evident that President Trump is determined to sign a virtual surrender document with the Taliban. This would permit him to ensure that there is no US combat military presence in Afghanistan when America goes for presidential elections, scheduled for November 3, 2020. Trump’s electoral support, drawn predominantly from a White Caucasian base, would like all their ‘boys’ back home to celebrate Christmas next year.

Figures show that US casualties from 2003 to 2018 were 2,372 killed and 20,320 wounded while an estimated 1.10 lakh Afghan soldiers and civilians paid with their lives. Is this example of the US entering conflicts and leaving the conflict zone without a decisive outcome something new? The Vietnam Conflict ended with an ignominious US withdrawal from South Vietnam. The then US ambassador, Graham Martin, was evacuated by helicopter from Saigon after North Vietnamese forces entered the South Vietnamese capital. An estimated 1.8 million Vietnamese were dead. US casualties were 31,952 killed and 2 lakh wounded.

Vietnam was united under Communist Party rule, which continues. But Vietnam did not become, as the US feared, a Communist Party ruled, Soviet/Chinese satellite. Vietnam has a close strategic relationship with the US today, aimed at containing Chinese expansionism in the South China Sea. This, after the Vietnamese gave the Chinese a bloody nose in 1979, when Deng Xiaoping promised to teach Vietnam a ‘lesson’ and invaded Vietnam.

One looks back at the Iraq conflict with similar sentiments. President Saddam Hussein was backed by the US during the Iran-Iraq war. The US, thereafter, forced Iraq to withdraw after it invaded Kuwait in the first Gulf War in 1990-1991. While the Iraqis reportedly lost about 1 lakh soldiers, US casualties were 383 killed. The Second Gulf War in 2003, based on false US allegations that Saddam was producing nuclear weapons, resulted in around 1.1 lakh Iraqi deaths. While Saddam, a Sunni, was anti-Iranian, the present Shia-dominated Iraq government avoids involvement in Arab-Iranian sectarian rivalries. US participation in conflicts has seldom produced the desired results.

Much has been written about Trump’s assertion during Imran Khan’s visit that Modi asked him to mediate on Kashmir. The Washington Post revealed last month that Trump had made 10,796 misleading statements since he assumed office in 2017! New Delhi has, therefore, been restrained in responding to his falsehoods, recognising that Trump has similarly offended countries like Canada and Mexico and European allies like France, Germany and Japan. He has no respect for international treaties like FTA, WTO guidelines, climate change and international agreement on Iran’s nuclear programme. The only ‘leader’ that Trump appears to admire is North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, who is not exactly a champion of democratic values!

It is too early to conclude how realistic Trump’s belief is that he can persuade Imran Khan, and more importantly, General Bajwa to facilitate a smooth withdrawal of US forces. Trump has bent backwards to please the Taliban and snub the elected government of President Ashraf Ghani, with presidential elections in Afghanistan scheduled for September this year. The Afghan army is, meanwhile, suffering huge casualties. Pakistan has moved deftly to persuade China, Russia, Turkey, Iran and Qatar to follow the US example of placing the Taliban and the Ghani government on the same pedestal. But Ghani has little prospect now of seriously influencing US policies.

The Taliban should not be regarded as omnipotent. It is an exclusively Pashtun organisation. Pashtuns constitute about 40% of Afghanistan’s population. The Taliban is tenacious, but survives with Pakistan’s patronage. Moreover, large sections of Pakistani Pashtuns, especially in the tribal areas bordering Afghanistan, are affiliated to groups like Tehrik-e-Taliban and Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, comprising Pashtuns with nationalistic inclinations, with scant regard for the Durand Line. These Pashtuns, on both sides of the disputed Line, will not take kindly to coercive Pakistani military actions against their brethren. With the exit of US troops, many Afghan Pashtuns are not likely to be responsive to Pakistan army’s demands to end their backing of Pakistani Pashtun brethren living across the disputed border.

Over the past two decades, India has won substantial goodwill across the ethnic divide in Afghanistan by adopting a non-interfering approach to developments within Afghanistan. The Taliban has never had a comfortable relationship with minority communities like Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turkmen and Shia Hazaras. Pashtun leaders like former President Hamid Karzai and Tajik leaders like Governor of Balkh province Atta Mohammad Noor and former Afghan intelligence chief Amrollah Saleh, regard India as a trusted friend. India’s economic and educational assistance to Afghanistan has won widespread regard. It would, however, also be prudent to keep channels of communication with the Taliban open.

Much is now dependent on how Trump plays out his withdrawal schedule. There are pressures from the State Department and the military to avoid a precipitous withdrawal and retain a residual presence. If Trump decides to fully pull out before the elections, the Americans could well be forced to leave Afghanistan ignominiously. If they phase out withdrawal and give time to the Afghan National Army and ethnic militias to be armed and trained, they would have created a credible force to face the Taliban. Finally, if southern Afghanistan is destabilised, Pakistan’s own stability will face challenges.

Imran Khan made a historic visit to the US and was successful in persuading White House of his commitment towards peace in the region. Washington didn’t ask Islamabad to do more this time but calling this a reversal of the US-Pak relations is far-fetched. There is still much more to do.

Michael Kugelman July 29, 2019

For proponents of the U.S.-Pakistan partnership, there’s much to be heartened about after Prime Minister Imran Khan’s recent visit to Washington.

There were smiles and kind words all around as he met with senior officials from across the U.S. government spectrum, including President Trump. Other members of Khan’s delegation, including Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, met with critical stakeholders as well.

The optics of the trip were extraordinary; from Khan getting feted by a packed room of elected officials on Capitol Hill to General Bajwa’s visit to Arlington National Cemetery to pay homage to U.S. war heroes.

Understandably, optimism broke out in Islamabad following what the Pakistani government rightly proclaimed a successful visit. Upon returning home, a euphoric Khan declared that he felt “not as if I have returned from a foreign trip, but as if I have returned after winning” the cricket World Cup.

U.S.-Pakistan relations have come a long way, especially given their dreadful state during the Trump administration’s early months. Still, it’s important not to overstate the improvements in the relationship. Khan’s visit cemented the two sides’ deepening cooperation in Afghanistan, as Washington rapidly pursues a deal with the Taliban to give President Trump the cover he needs to announce a troop withdrawal.

But beyond Afghanistan, the obstacles to greater cooperation remain considerable. It’s worth examining these obstacles in detail, and also what we can expect this slowly stabilizing but a still-volatile partnership to look like in the coming weeks and months.

A core challenge is reconciling an expectations disconnect. Islamabad is keen for a reset and broadening of the relationship, while Washington—even after Khan’s successful visit—remains fixated on orienting the relationship around reconciliation in Afghanistan and Pakistan-based terrorism. The Trump administration has stated that there is potential for cooperation beyond these two issues, but only after Washington sees Pakistan making more progress addressing them. And on this count, it will be a tall order for Islamabad to deliver in ways that Washington would like.

Afghanistan may be the easier nut to crack. U.S. officials want Islamabad to convince the Taliban to agree to a ceasefire and to negotiate directly with Kabul. That’s a mighty big ask, given that the insurgents—who enjoy ample leverage in talks thanks to all the territory they hold and a lack of urgency, relative to Washington, to get a deal—have plenty of incentive to say no.

Washington’s message is simple. Pakistan expunged Pakistan Taliban why it can’t also target the Afghanistan- and India-focused militants on its soil as well

Still, after seven rounds of U.S.-Taliban talks and a recent intra-Afghan dialogue that produced a roadmap for peace document, there is unprecedented momentum. So, Islamabad may be able to make some headway—though it won’t be easy.

The terrorism issue is trickier. U.S. officials haven’t been satisfied with Islamabad’s recent crackdowns, which have included the arrests of dozens of militants and closures of their facilities. The White House is looking for what it describes as “irreversible” steps against the entire terrorist infrastructure. It includes the prosecution and convictions of top terrorist leaders and the dismantling of all training facilities and financial networks.

Pakistan may be under pressure to crack down heavily because of pressure from the Financial Action Task Force, the terrorist financing watchdog, but U.S. officials remain skeptical. Even if there is progress on Afghan reconciliation, Washington will remain relentless in pressuring Pakistan on the terrorism front.

Indeed, for many U.S. policymakers, this is an emotional issue. A fervent belief motivates these officials that Islamabad has long been complicit in cross-border attacks, carried out by Pakistan-based militants, on U.S. troops in Afghanistan. Trump administration officials have stated that the president’s principal foreign policy goal is to protect Americans overseas. That position, in line with Trump’s “America First” strategy, suggests that Washington won’t ease up on the pressure until it’s satisfied that Americans in Afghanistan are no longer threatened by militants in Pakistan.

Washington’s message is simple. Pakistan demonstrated it has the will and capacity to expunge anti-state terrorism, given its admirable efforts to all but eliminate the Pakistani Taliban threat, so there is no reason why it can’t also target the Afghanistan- and India-focused militants on its soil as well.

Washington understands that Islamabad faces risks in targeting the latter types of militants as opposed to the anti-Pakistan ones—from alienating valuable assets to provoking blowback against the Pakistani state—but this won’t make U.S. policymakers less insistent that they are targeted in irreversible ways. To be sure, however, progress in Afghanistan leading toward a peace deal may ease these terrorism-related tensions.

If the Taliban and its allies are no longer fighting U.S. troops, then the threat to Americans from Pakistan-based, Afghanistan-focused militants would become moot. However, the issue of India-focused militancy—another core U.S. concern—would remain salient.

All this said, imagine that Islamabad helps produce a deal in Afghanistan and takes counterterrorism steps that satisfy Washington. Even then, U.S.-Pakistan relations would face significant constraints due to geopolitics. Indeed, one can’t overemphasize enough the fundamental policy divergences between the two countries. These divergences are encapsulated by Washington’s rapidly growing security ties with New Delhi and Islamabad’s alliance with Beijing.

Read more: Personal connection Done, Time to achieve goals: US to Pakistan

Despite some recent bumps in these relationships—from Beijing’s concerns about the safety of Chinese workers in Pakistan to worsening U.S.-India trade tensions—the overall trend lines for these partnerships remain strongly positive. In effect, Washington and Islamabad enjoy deep partnerships with each other’s main adversary. They are also each pursuing foreign policies in Asia that depend heavily on these partnerships, and that goes against the other’s interests.

The Trump administration has taken a hard line on Beijing, America’s top strategic competitor. Significantly, the Trump White House’s first national security strategy, which was released in 2017, described strategic rivalry—not terrorism—as America’s biggest national security threat. This suggests that for Washington, Beijing isn’t a mere competitor; it’s an all-out threat. Not surprisingly, the Trump administration’s Asia policy—its Indo-Pacific strategy—revolves around pushing back against China, with hoped-for assistance from India. Meanwhile, Islamabad’s core policy involves undercutting India in the region, with Beijing’s support.

These geopolitical realities mean we’re unlikely to see the kind of moves that could help strengthen U.S.-Pakistan relations. Washington isn’t about to press New Delhi to ease up on its repressive activities in Kashmir, or—despite President Trump’s recent offer—to position itself as a mediator in that dispute, one that New Delhi believes is non-negotiable. Similarly, Islamabad isn’t about to shut down the CPEC enterprise or curtail Chinese influence in Pakistan.

Khan’s visit cemented the two sides’ deepening cooperation in Afghanistan, as Washington rapidly pursues a deal with the Taliban to give President Trump the cover he needs to announce a troop withdrawal

Additionally, these problematic geopolitical realities preclude the ability of Washington to regard Pakistan as a nation worth engaging more broadly because of the critical strategic player that it is—thanks in significant part to its size, location, and key bilateral partners.

At the very least, figuring out how to square this circle—how to deepen a partnership despite a geopolitical state of affairs heavily stacked against it—will require a lot of bilateral discussions, and over a long period of time. This is another obstacle for U.S.-Pakistan relations: The Trump administration, unlike its predecessor, is not a fan of the extended, careful, and private dialogue that can encourage new thinking and help build up much-needed goodwill and trust (it bears mentioning that in Washington, many policymakers’ views of Pakistan remain hostile and jaded, despite increased bilateral cooperation on Afghanistan). Instead, it prefers transactional diplomacy and summitry.

What, then, can we expect for U.S.-Pakistan relations, given the genuine improvements in recent months coupled with the major constraints? In the coming weeks, expect bilateral ties to enjoy more wins amid intensified efforts to get a deal in Afghanistan. Some goodwill gestures, meant to signify each side’s commitment to partnering with the other in the Afghan peace process, are likely to ensue. Several such moves—Islamabad’s (latest) arrest of Jamaat-ud-Dawa leader Hafiz Saeed and Washington’s decision to provide $125 million in technical support for Pakistan’s F-16 fleet—have already been made.

Future steps might include easing up on restrictions imposed on the movements of each other’s foreign diplomats or intensifying the frequency of bilateral consultations under the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA).

Further afield, if—and that’s a big “if”—Pakistan helps get a deal in Afghanistan and sufficiently addresses Washington’s concerns about terrorism in Pakistan, the relationship could experience a dramatic boost. Under this scenario, Washington would likely unfreeze its suspended security assistance to Pakistan and resume some broader security cooperation. This may include sharing intelligence on the movements and locations of regional terror threats—such as ISIS—that both sides view as threats, and that would not be a party to any peace deal in Afghanistan.

Additionally, the two sides may aim to expand their trade relations, which totaled nearly $7 billion last year—a new record. Based on recent White House statements, Washington may be particularly inclined to ramp up energy trade, and specifically LNG.

Perhaps the biggest medium-to-long-term question for U.S.-Pakistan ties is the impact of a U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan on the bilateral relationship. On the one hand, with no more American soldiers in Afghanistan, a core reciprocal tension point—Pakistan’s role in the Taliban insurgency and its complicity in attacks on Americans—could wither away.

At the same time, if U.S. troops leave before the Taliban has agreed to stop fighting, the troubling spillover effects in Pakistan of a rapidly destabilizing Afghanistan could generate accusations in Pakistan of Washington’s having abandoned the region once again; just as it did after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan several decades ago.

Furthermore, imagine if Washington, with no more troops in Afghanistan and therefore unencumbered by the risks to U.S. forces there if Islamabad retaliates harshly to hardline U.S. moves, tries to tighten the screws on Pakistan in order to compel it to crack down harder on the India-focused militants on its soil.

The future trajectory of U.S.-Pakistan relations; much like that of the Afghanistan quagmire to which those relations are firmly tethered, is riven with uncertainty. There is potential for growth, but how much is unclear. Likewise, significant constraints will remain, but how severe they will be is unknown.

Ultimately, the relationship’s challenges amplify the importance of two core nonofficial (that is, non-government) components of the U.S-Pakistan partnership—the U.S.-based Pakistani diaspora and the U.S. and Pakistani private sectors. If given the proper incentives, the Pakistani diaspora and American and Pakistani companies can—through stepped-up investment, joint ventures, and other forms of engagement—help bring more trust and goodwill to a formal relationship, severely lacking in both.

Read more: $125m support for Pakistan’s F-16 fleet approved by US

In fact, those proper incentives are already emerging: Consider the diaspora’s enthusiasm for Imran Khan, and the increasing market and investment opportunities afforded by Pakistan’s young population and improved security situation.

The U.S.-Pakistan relationship can likely only go so far. Still, its relative growth potential is real—and especially if each side taps into underutilized resources outside the official partnership.

The article appeared in the Global Village Space on 29 July 2019

Go to Source

Author: Michael Kugelman

Tribune News Service

Moga, August 1

Deputy Commissioner Sandeep Hans on Wednesday called upon the youth from the district to participate in the upcoming recruitment rally of the Indian Air Force (IAF) which will be held at the Punjab Armed Police Grounds in Jalandhar on August 5.

The Deputy Commissioner said Moga was among the 12 districts in the state selected for the recruitment rally being held for posts under Group ‘Y’ (non-technical) (automobile tech and IAF police).

Sandeep Hans said the youth who were born between July 19, 1999, and July 1, 2003, could participate in this rally. He said physical fitness test and written test for youth of the district would be held on August 5 and their adaptability test I & II would be held on August 6.

Chandigarh, August 24

The Indian Air Force’s (IAF) largest helicopter maintenance and overhaul establishment No.3 Base Repair Deport (BRD) in Chandigarh has been adjudged the best repair depot among 13 such depots of the IAF.

The trophy for the best BRD was presented by Chief of the Air Staff Air Chief Marshal BS Dhanoa to the Air Officer Commanding, 3 BRD, Air Commodore Sanjiv Ghuratia at the Commanders’ Conference – 2019 held at the Maintenance Command Headquarters in Nagpur.

The Air Chief highlighted the significant role played by the Maintenance Command, presently headed by Air Marshal RKS Shera, in meticulous management of the vast and varied inventory of the Air Force.

Appreciating new initiatives by the Command to keep pace with the rapidly changing technological scenario and induction of new aircraft and systems, he underscored the vital role played by the engineers in keeping the IAF combat ready and emphasised the importance of team. Lauding the efforts of the Maintenance Command in supporting other combat commands in maintaining high state of operational readiness at all times, the Air Chief exhorted them to keep upgrading their skills in the fast-changing technological environment.

Set up in 1962, 3 BRD is responsible for the repair, maintenance and overhaul of Soviet and Russian origin helicopters as well as AN-32 aero-engines in the IAF’s service. Besides aircraft modifications and fleet upgrade projects, it is also actively involved in the indigenisation of aerospares. — TNS

KV Prasad

Tribune News Service

New Delhi, August 21

Raising tension in South China Sea, China has stationed two Coast Guard ships near the ONGC Videsh oil exploration block off the Vietnam coast, besides increasing military activities, including conducting sorties.

Diplomatic sources of Vietnam said here that personnel from these two ships were using loudspeakers asking halting of work on the 0.61 block, where ONGC Videsh works in a joint venture with Russian Rosneft and Vietnam companies.

India is associated with exploration work here for the past 17 years and in the past too Beijing protested commercial oil exploration activity.

Concerned over the presence of some 20 vessels, including eight coast guard ships, 10 fishing boats and two service ships in the area, sources said China returned to the area recently after staying put for 33 days from July 3.

Hanoi says the area where Beijing is moving around fall in Exclusive Economic Zone, a claim disputed by Beijing.

To prevent China from extending claim, Hanoi decided to increase diplomatic pressure amid indication that the issue could be taken to the UNSC. “There is a suggestion that we follow the same China-Pakistan model at UNSC, if Pakistan can take bilateral issue to UNSC, South China Sea is still an international issue,” the sources said.

Vietnam sources said while intention of China was to force Vietnam to draft it as a partner in exploration, they were not certain whether the idea of moving coast guard ships close to the Indian block is linked to New Delhi’s move in J&K.

Locals in Kashmir, Oppn call it a ‘black day’; Jammu celebrates

NEWDELHI: In a move planned with political and legal precision, and complete suspense, the central government led a move in the Rajya Sabha on Monday to end the special status of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). By the end of the day, Article 370 and Article 35A, which have, for close to seven decades, defined the state’s relationship with the Union, were effectively rendered null and void.

It also pushed through a bill in the Rajya Sabha to reorganise the state. J&K has now been bifurcated; Jammu and Kashmir will be a Union Territory (UT) with a legislature; and Ladakh will be a separate UT without a legislature. The resolutions are to be tabled in Lok Sabha on Tuesday, where the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has an overwhelming majority.

The move came after a week of intense security build-up in the state — additional paramilitary troops were deployed, the Amarnath Yatra was cut short, tourists and non-Kashmiri students were advised to leave, Kashmiri leaders, including former chief ministers Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti, were detained, internet and phone connections were suspended, and movement severely curtailed. The actions caused panic in the Valley and prompted speculation about whether the government was pre-empting a terror threat from across the border, or seeking to bring in drastic legislative changes.

Monday provided the answer.

The day began with a Cabinet meeting at 9.30am at Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s residence in New Delhi’s Lok Kalyan Marg. Union home minister Amit Shah then headed to Parliament, where he began speaking in the Rajya Sabha at 11am. While Opposition leaders first sought a response to the unfolding situation in the Valley and the detention of Kashmiri leaders, Shah said he would address all the concerns.

He then moved four motions. The first was the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019, which superseded the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order of 1954. The 1954 order gave rise to Article 35A, which defined and prioritised permanent residents.

The order also enabled all provisions of the Indian Constitution to be applied to Kashmir. With this, not only was the supremacy of the Indian Constitution and its laws reinforced, but the special provisions which gave the state a distinct constitutional identity, removed.

The order also added a clause to Article 367 of the Constitution — whereby it said that references to the Government of Jammu and Kashmir would be construed as the governor of the state (acting on the advice of a council of ministers); and the reference to the constituent assembly of Jammu and Kashmir of Article 370 would now read legislative assembly of the state.

The second was a statutory resolution to recommend to the President to issue a notification, using clause 3 of Article 370, to declare that all clauses of Article 370 would cease to be operative and that all provisions of the Indian Constitution would apply to the state of Jammu and Kashmir.